The Dakhla Oasis lies west of the Nile river, between Cairo and Luxor. Egyptologist Garry Shaw follows the trail of one of the earliest visitors to the Oasis, Archibald Edmonstone, around Egypt’s ‘wild west’

It was dawn when I left the White Desert for Farafra. The rising sun had already revealed the petrified zoo of chickens, horses, and sphinxes that had commanded my attention the previous evening. Eroding limestone giants, stretched and unfolded themselves for the new day. The desert foxes, gaunt-faced and curious, had long since scurried away, fed, if not full, from scraps of bread offered by Saleh, my driver. White, jagged splats of limestone appeared like frozen waves upon a yellow ocean. The air was crisp.

The Haggar Temple

A short drive later and I was in Farafra, a half-finished vision of a Wild West outpost, where Saleh, paid and pleased, dropped me off and departed back for Bahariya Oasis, performing an illegal-in-forty-countries U-turn in the process. There, following true Western movie convention, as a stranger in an unfamiliar town, I was immediately picked up by the local police and questioned on my reasons for being in the oasis; more importantly, they wanted to know when I’d be leaving and suggested that I take the 2pm bus.

This article first appeared in the winter 2014 edition of Timeless Travels magazine.

I had no real problem with this, as I’d planned on taking public transport for the next leg of my journey anyway, but soon after, over Turkish coffee in a local cafe, I was invited by two sporty Spanish honeymooners and their rotund guide, Mohammed, to join them on their whirlwind tour of the oases. After all, we were heading in the same direction: Dakhla Oasis, the third oasis on my trip through the Western Desert, where a variety of ancient sites neatly illustrate Egypt’s long history with these isolated Saharan islands.

Accompanying my travels in digital form was the 1822 travel narrative of Archibald Edmonstone, the first European to visit Dakhla in modern times, who coincidentally was born on the same London street that the British Museum still stands. Edmonstone, a wealthy baronet, arrived in Egypt in late 1818, aged 23, with the intention of exploring the oases as “objects of curiosity” and to look for “old buildings.” A true Brit, he also wanted to get there before the French consul and Dick Dastardly-alike Bernardino Drovetti, who was busy hoovering up as many artefacts and accolades as he could for himself (and France, of course). Informed that Drovetti had set out for the oases a few days before him, Edmonstone decided to cross the desert directly to Dakhla, rather than take the safe route to Kharga first, as Drovetti had done. This was risky for two reasons: 1) it would mean a longer trek through the desert, and 2) no European was certain that Dakhla Oasis existed. If Edmonstone’s gamble paid off, and he didn’t end up a scorched pile of carrion picked desert bones, Britain, and adamantly not France, would be the first to celebrate the addition of a new patch of green to its maps of the Sahara Desert.

Scenery at the Dakhla Oasis

Travelling to the Oasis

As I lay in the comfort of my spacious, air-conditioned van, whizzing along a modern tarmac road, I imagined Edmonstone, with his two European companions, two Egyptian servants, interpreter, and twelve camels setting out into the relative unknown (presumably his Bedouin guides were less nervous), marching through the sands for thirteen hours a day.

Unlike the minor inconveniences I’d experienced in the oases, Edmonstone was truly travelling through a dangerous and wild frontier. Three years before his visit, four hundred raiders from Libya had plundered Dakhla, killing people and “carrying off much booty”. Two years afterwards, in 1821, the Pasha, Mohammed Ali, had sent troops to subdue the entire area. To reduce the risk of trouble, it was “strongly recommended” to Edmonstone that he wear Mamluk clothing; his “look” included “a coarse silk waistcoat with long open sleeves… an immense pair of cloth trousers, red slippers, and a turban of white muslin.” He also slung a Turkish sabre across his shoulder, hid a dagger beneath a shawl tied around his waist, and hung a brace of pistols under his left arm. Unlike Edmonstone, I was dressed in a faded blue t-shirt and a tatty pair of jeans. Desert travel has certainly changed.

Driving to Mut, Dakhla’s capital, we passed farmers wearing wide straw hats, a local fashion noted by Egyptologist Herbert Winlock in 1908. The soil was pink, almost purple, and the gamoosa (water buffalo), so prevalent elsewhere in Egypt, had been replaced by cows. Squat pink-mud huts with palm roofs stood in the fields between villages of colourfully painted domed-houses. Along the way, we briefly stopped at the el-Muzzawwaqa tombs, a small splat of a hill, as if sculpted from mashed potato, pierced by Roman era tombs.

Edmonstone, the first to comment on this “insulated rock perforated with caverns”, observed scattered fragments of human remains littering the earth, remarking, “The inhabitants of the adjacent hamlet had stripped them in hopes of finding something valuable; and the jackals, which abound here, had completed the work of devastation.” He attempted to take some bones, but his guides threatened to abandon him if he did so. I too was shown a pit of assorted remains. They stared up at me as if saying, “wonderful, another gawker.”

The Medieval town of el-Qasr

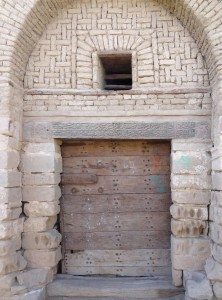

Doorway in el-Qasr

At the north edge of Dakhla Oasis, our next stop, the medieval town of el-Qasr (“The Fortified Town”) came into view. After turning off the main tarmac road, and driving through a palm grove, the honeymooners, Mohammed and I left the van and rounded a modern white mosque. Splendidly wonky and sepia toned, the town, founded in the 12th century above a Roman fort, is an unusual sight: part-reconstructed, mostly abandoned, yet still occupied by a few hundred people.

It is a living village, protected by antiquities guards working for the Ministry of Antiquities. Every house exuded age from its cracked mud-brick pores, revealed by their shedding plaster. Many doorways were low to the ground, barely a couple of feet high; men in galabeyyas squatted beside them in the shade. Heavy doors sealed the town’s various quarters, keeping its population – 4,000 strong in the 19th century – safe from bandits. It was like being led through a half-remembered dream of an Ottoman fantasy. Two hundred years earlier, upon “discovering” el-Qasr, Edmonstone had been less enchanted: “The only thing worthy of observation in the town is a strong sulphuric and chalybeate spring, which the people consider extremely sanative, and drink when left to settle for 24 hours in an earthen jar.”

As I followed the cuddling Spanish and the sweating, narrating Mohammed around the narrow streets, the imposing walls of multi-storey houses loomed, draping us in continuous and cooling shadow; the German explorer Gerhard Rohlfs, along with his entire team of 100, had briefly stayed in one of these houses during his desert explorations in 1874. Some houses displayed acacia lintels over their doorways with inscriptions informing passersby of the occupant, as well as the name of the artist who carved the inscription; the oldest dated to 1518. Presumably Rohlfs wasn’t present long enough to commission his own lintel.

Our first stop was the mosque and mausoleum of Sheikh Nasr ed-Din, who was himself present yet absent, buried in a shrine, enveloped by a green sheet. It was surrounded on the walls by Quranic verses, which dipped in and out of niches with artistic abandon. Although the mosque had been rebuilt in the 19th century, its minaret maintains its 11th-12th century structure, though it too has undergone reconstruction; two layers of wooden beams jutting out from its body.

A madrassa (school) was next door. This had been renovated, and is still in use today. Conveniently for the medieval population, it also functioned as a meeting place, a courtroom, and as a place of punishment, all no doubt classified under “entertainment” by the townsfolk. To add to the ambiance, prisoners were once tied to a stake still standing beside the entrance, a definite warning to any would-be unruly school children.

In the maze of streets, Mohammed, clearly as geographically gifted as a globe, next led us to a house that incorporated ancient Egyptian temple blocks in its facade, some exhibiting figures and hieroglyphs; one block displayed the torso of a squatting baboon-shaped Thoth, his hands casually resting on his knees as if patiently waiting for his head and legs to return. Others were penetrated by long vertical scratches, made by people in antiquity collecting magical temple-powder. The now crumbling town also once had a mill (with an ox or donkey-powered mechanism), and an oil press.

The Roman temple at Deir el-Haggar

Our next stop was Deir el-Haggar – “The Monastery of Stone”. Edmonstone found this temple, “in tolerable preservation, though half filled with sand”, which he tried to clear, but quickly gave up. I found it with a motorbike parked inside the visitor centre; a dusty blue basket rested on its back, making its presence at least excusable as an ad-hoc storage space.

The walls within were salmon-pink and hung with information panels, which explained the temple’s history and recent restoration work.

Entrance to the temple at Deir el-Haggar

Despite taking the form of a typical ancient Egyptian temple (court, hypostyle hall, sanctuary), Deir el-Haggar was erected under Roman Emperor Nero (54-67), and decorated under his successors, Vespasian, Titus and Domitian in honour of the gods Amun, Mut and Khonsu. Stepping outside the visitor centre, I spied distant Roman tombs dug into the sandy hills; in the early first Millennium, farms and priests’ houses stood on these now barren plains between the temple and the tombs. After “inheriting” Egypt, the Romans had actively encouraged Nile Valley Egyptians to relocate to Dakhla to produce cereals, oil and wine, meant to feed the imperial machine. Massive aqueducts were built near the temple, connecting springs and fields.

I spotted the word “Caesar” written in hieroglyphs within the royal cartouches. Small orange-beaked birds chirped in dusty holes. Bats hid in subtle cracks. They were rare signs of life in a now desolate place.

This prosperity wasn’t to last, however. Early in the 5th century CE, massive sandstorms engulfed Dakhla’s farms and temples, apparently while they still functioned. Deir el-Haggar was among those enveloped, causing its north wall to collapse and its ceilings to fall.

Abandoned to the elements, it became a ruin, ignored until Edmonstone’s visit and only properly documented in 1908. And this wasn’t the end of its woes; between 1965 and 1968, antiquities looters attacked the temple on nine occasions, cutting away 32 fragments of the best preserved parts of the walls. Only recently had Deir el-Haggar been reconstructed and its fabric properly protected. To combat the shifting sands, archaeologists had erected a palm-branch fence around its perimeter. Spare temple blocks, unplaced during the reconstruction, lay at its edge, awaiting some Lego savant. A guard’s hut, a TV antenna optimistically protruding from its roof, symbolised newfound protection.

Over the next hour, I wandered through the temple, its columns rising to a vacant ceiling, some still bearing the remains of ancient plaster and paint. Broken pottery littered the floor. I spotted the word “Caesar” written in hieroglyphs within the royal cartouches. Small orange-beaked birds chirped in dusty holes. Bats hid in subtle cracks. They were rare signs of life in a now desolate place.

Outside, I found the names of Rohlfs’ expedition members carved high on a column, dramatically illustrating the height of the sand in his day. The names of other early explorers can also be found at the temple, simultaneously presenting a compendium of desert exploration and incriminating the high class vandals. Among them were the names of both Edmonstone and Drovetti.

Following his return from the oases, Drovetti had written that his visit to Dakhla had occurred “toward the end of 1818”, contradicting Edmonstone’s claim to have beaten him there, as he had only arrived on 16th February 1819. This created a controversy that was only settled one hundred years later, when a graffito at Deir el-Haggar, dated 26th February 1819, was found to bear the name Rosingana; as Rosingana had accompanied Drovetti to Dakhla, this provided the proof that the French Consul had indeed exaggerated the date of his arrival to bolster his claim of being the first European to visit the oasis. Dick Dastardly-like indeed!

Before leaving, in an overlooked gateway penetrating the temple’s mud-brick temenos wall, I found images of gods, sacred animals and Greek inscriptions painted by the Roman-era devout. One of the earliest was a bearded image of the god Sarapammon-Hermes, upon which later worshippers had added pictures of a ram – symbol of Amun-Re – and a Thoth baboon, along with four floral wreaths with looped ends. At first, I was moved by the presence of these crudely painted images of devotion and the darkened patches of plaster left by the touch of pious, ancient worshippers. Then I realised that Sarapammon-Hermes, now overlaid with floral wreaths protruding from either side of his torso, appeared like the robot from Lost in Space.

It was time to move on.

The Old Kingdom tombs near Balat

Our final stop was Balat, on the eastern side of the oasis. As we neared, a thriving village presented itself; the dusty streets were topped by palm branches, stretched between the roofs of mud-brick houses painted in hues of pink and red. It was here that Edmonstone had set up camp upon arrival at Dakhla.

Soon after, the local sheikh had brought the frazzled explorer some much-needed food; in return, Edmonstone had given him “an Indian handkerchief, with which he seemed pleased”. Without Edmonstone realizing, in the vicinity of his camp were the buried remains of some of the oasis’ most ancient structures – a series of great tombs dated to the 6th Dynasty, each belonging to a regional governor. This cemetery is now known as Qila’ el-Dabba.

I followed Mohammed and a galabeyya-clad tomb guardian across the pink sand to the tomb of Khentika. Discovered in 1977 by Egyptologist Ahmed Fakhry, and dated to the reign of King Pepi II, the tomb resembled an upturned jelly mould; in antiquity, workers had excavated a giant stepped pit and constructed the burial chamber at its base.

Afterwards, they had filled the space with mud-bricks. The guardian descended a set of shallow steps towards the burial chamber’s dark entrance way, his sandals alternately shuffling and slapping against their uneven surfaces. Within, in the dim light, little paint remained. Broken images of Khentika, painted in brown and blue and with surprisingly large eyes, stared out at me from the reconstructed walls. Crudely executed figures and boats were testament to the oases’ provinciality; after all, the best artists lived at court in Memphis, far away from Dakhla.

There is very little evidence for contact between the Egyptians and the people of Dakhla before the late Old Kingdom (2584–2117 BCE). But in this time, around twenty towns, mainly in the western side of the oasis, were built. The most important settlement was at Ain Asil, about 1.5 km from Qila’ el-Dabba and Balat. It was there that Dakhla’s newly installed governors managed the oasis, and indeed, the oases as a whole. To promote their status, around their administrative headquarters they built funerary chapels – cult places where the locals could generously offer food to their spirits in death; conveniently, bakeries were constructed around these chapels to facilitate this process.

Mohammed, the honeymooners, and I next entered the tomb of governor Bitsu, which on the surface looked like a WWII bunker. Within, little remained but a sarcophagus, painted on its interior with roughly drawn hieroglyphs and an image of Bitsu himself, sat on a chair beneath a canopy. All seemed appealing, except for Bitus’s ridiculously long legs, which flowed from his torso along his chair to the ground like a barely contained flood. Clearly, his inexperienced artist had painted the chair and the inscriptions first, and then had to figure out how to fit Bitsu into the remaining space. As clumsy as this might seem, for a short time at least, Bitsu’s unusual tomb art was in vogue.

Not long after these paintings were finished, Egypt’s great Old Kingdom collapsed and the country fragmented into competing regions. Without the patronage of the royal court at Memphis, artworks across Egypt began to be produced in a similarly crude style to those at Dakhla. The arts would not recover until the Middle Kingdom, one hundred years later.

Moving on

My day of unexpectedly efficient sightseeing at an end, I bade farewell to Mohammed and the Spanish honeymooners in front of my hotel at Mut. My chance encounter with Mohammed had streamlined my visit, removing any need to concern myself with public transport or hiring a guide. I again thought of Edmonstone, only 23 years old, bedecked in assorted weapons, riding

his camel into the unknown, and felt a bit of a sham-adventurer. I was suddenly pleased that my “run in” with the police at Farafra had added some extra spice to the day. Exploring the desert should not be easy, and indeed, the oases do still truly feel like an Egyptian Wild West, but one that has been tamed somewhat, accessible to all wanting to escape the beaten tourist path. An achievable adventure for the cautious explorer.

The next day I planned on heading to Kharga Oasis to finish my loop. Edmonstone spent four days exploring Dakhla before making a similar move. On the way, half a day’s journey from Balat, he bumped into Drovetti, still crossing the desert, still hoping to be the first. Despite Edmonstone’s mention of a “conversation” between them, neither explorer records Drovetti’s reaction. Says it all really.

This article was first published in the winter 2014 edition of Timeless Travels magazine.

© 2014 Timeless Travels, republished with permission.