Most, if not all, of our readership knows about the intentional destruction of ancient artifacts, buildings, mosques, shrines, and the contents of Mosul museum contents by the so-called Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS). The Governorate of Mosul in Iraq is the site of several ancient Assyrian cities (Nimrud, Kouyunjik, and Dur-Sharrukin), in addition to Hatra. The 3,000 year old ancient city of Kalhu (modern-day Nimrud; Biblical Calah) received the bulk of the blow, and a propaganda video issued by ISIS in April 2015 showed the dramatic and shocking explosion of the northwest palace of the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II.

The in situ artifacts of Nimrud were composed of palace wall reliefs, mainly from the northwest palace of Ashurnasirpal II,and few lamassu, which are mythical human-headed and winged bulls or lions. Thanks to the great work and excavations conducted by archaeologists from many parts of the world, in addition to Iraqis, artifacts from the Assyrian city of Nimrud are now displayed to the public in many museums and private collections all around the globe.

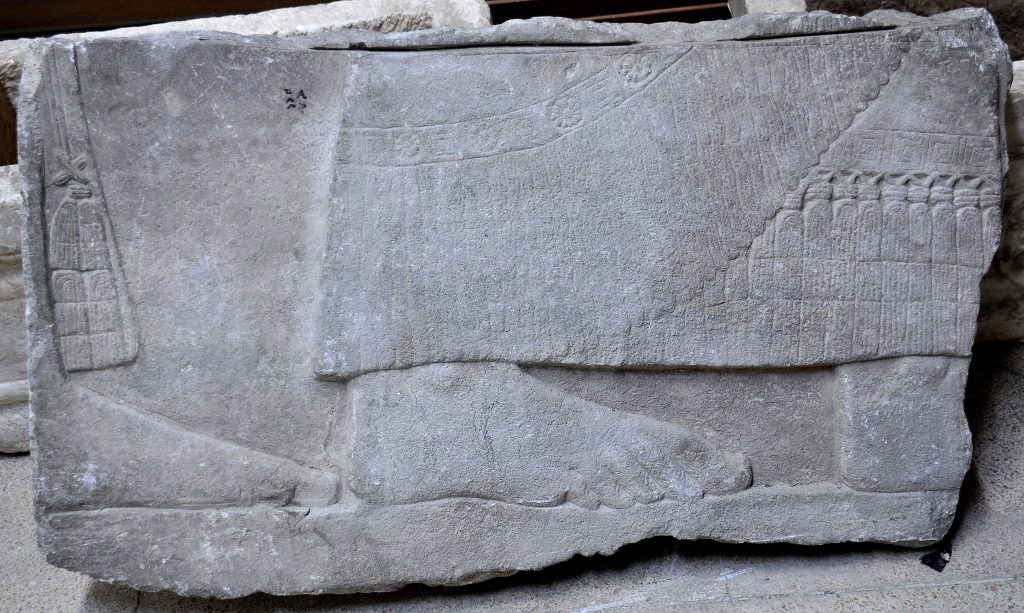

Detail of a gypsum wall relief from the northwest at Nimrud. What has survived is the left hand of an apkallu (Akkadian word meaning “sage”). The hand grips on the handle of a buckle. The buckle is supposed to contain a fluid, perhaps water for purification. The cuneiform text of the so-called “standard inscription” of Ashurnasirpal II runs over the relief. At the right upper angle, part of the “sacred tree” appears. From the northwest Palace at Nimrud (room and panel numbers are unknown). Northern Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq. Assyrian, 865-860 BCE. On display, the Sulaymaniyah Museum, Iraqi Kurdistan. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The Sulaymaniyah Museum in Iraqi Kurdistan houses eight small fragments from the Assyrian palace’s wall reliefs. Only one out of these eight pieces is on display within the main hall of the museum; the others were never displayed, and they did not undergo any conservation. I asked Mr. Hashim Hama Abdullah, Director of the Sulaymaniyah Museum, about the history and journey of these reliefs in late 2014. We desperately examined and searched through the archives and documents of the museum from 1961 to the late 1990s; unfortunately, our attempt was fruitless. Nothing documents their acquisition and presence, which was a shock.

Afterwards, Mr. Hashim suggested that I should speak to Mr. Mutasim Rasheed Abdulrahman (Arabic; معتصم رشيد عبد الرحمن), former acting director of the museum during the 1980s. Hashim said Mutasim was the person who expanded the museum’s content, and he was quite sure that Mutasim had more information about these reliefs. Hashim phoned Mr. Mutasim and then arranged an interview for me.

During the Iraq-Iran War (1980-1988), the Sulaymaniyah Museum was officially closed to the public. The Governorate of Sulaymaniyah is on the Iraq-Iran border and was one of the bloody war zones between the two nations; additionally, it was the locus for the Kurdish rebellion against Saddam Hussein’s regime in the late 1980s.

“During the mid-1980s, I was transferred from Baghdad to the Sulaymaniyah Museum. The museum was closed at that time because of the war, and its contents were very minor and small… most of which were replicas. The museum had not acquired new artifacts [for] maybe more than a decade. I took permission from Mr. Muaid Saeed Al-Damirchy, former General Director of the Directorate of Antiquities of Iraq, to acquire and transfer ancient artifacts from the Iraqi Museum in Baghdad and Mosul Museum in Mosul Governorate to the Sulaymaniyah Museum. The permission did not state which artifacts to be taken. Literally, I could choose anything. When I went to the store rooms of the Mosul Museum, I found many fragments of Assyrian wall reliefs. I don’t know where exactly they came from, but perhaps Nimrud or Nineveh? The reliefs were transferred first to the Iraqi Museum in Baghdad at some point in time, but again, I don’t know when. The Mosul Museum later acquired these eight fragments and stored them. They were never displayed, never published, never restored, and obviously neglected, for reasons that I still don’t understand. Their storage was strange and full of negligence, in addition to being unnoticed. Mr. Muaid, however, was very cooperative and ordered them to give the reliefs to me. This was… in maybe 1986 or 1987 — I don’t remember honestly.”

Replying to my question of why Mutasim choose these reliefs, he said:

“The Sulaymaniyah Museum did not house any of the Assyrian wall reliefs, only two replicas, which were taken from Baghdad, maybe one or two decades before. The replicas portrayed hunting animals and one other the party of an Assyrian king (Nota Bene: He was referring to one of the Lion-Hunting Scenes of Ashurbanipal II and the Banquet Scene of Ashurbanipal II). Therefore, when I saw these reliefs, in this miserable condition, I decided to take them with me. I chose the best pieces available. The inscriptions were clear on most of them, meaning that they could be read, transliterated, and published. It was my idea to tie our names with Ashurnasirpal II’s name.”

I then asked him, what happened after their arrival to the Sulaymaniyah Museum?

“There was no archaeology college in Sulaymaniyah at that time, and no one was there or ready to undertake the necessary research. After three or four years, the Iraqi army invaded Kuwait, economic sanctions affected the entire country, the Gulf War began, the Kurdish uprisings ensued, and the Federal Kurdish Government of Iraqi Kurdistan was established… all of this created a turbulent environment. The situation soon reached a boiling point. After 1992, I could not find any support from anyone, the local government or parties…no one was thinking about archaeology…it was a time of immense chaos with everyone focused on Kurdish independence… the financial crisis… and so on. Finally, I gave up and surrendered. I retired in the mid-1990s. My story ends there. Osama, are the only and the first one to ask about these Assyrian reliefs. Hashim said that you are a ‘brain physician’ or something and a military personnel, correct? You popped out from no where and you are asking about these reliefs after nearly 30 years!”

I flattered that he provided me with this useful information. I thanked him a lot and wished him a happy and healthy life.

This hall of the Sulaymaniyah Museum was renovated by the UNESCO as part of a specific master-plan in 2013. The hall houses the masterpieces of the Sulaymaniyah Museum. The fragment from the wall relief, which came from the northwest palace sits on right lower angle of this wooden platform. Stamped bricks from Ur, a door sill from Kurikalzu, stone blocks from the Sassanian Paikuli Tower, and an inscribed Assyrian pavement brick are also displayed on that paltform. The visitors are gathering around the Stela of Iddin-Sin, king of Simurrum. The Sulaymaniyah Museum, Iraqi Kurdistan. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

In summary:

- The reliefs were neo-Assyrian. All came from the northwest palace at Nimrud. Only the origin of one of the reliefs is disputed, because of its type of the stone, depiction, color of the relief, and its style of carving.

- Two out of the eight reliefs showed the label of the Mosul Museum. The others were not labeled. In addition, all of them did not show any sign or label of the Iraqi Museum (“IM”).

- The shape of the reliefs were roughly rectangular with somewhat similar dimensions of about 100 x 50 cm. (This is a rough estimate as I did not measure them). All of the reliefs’ margins showed a similar cut, except the disputed one, which pointed towards the usage of an electric saw. This means that this relief was handled by a modern tool, before or after a relatively recent excavation at that time. Is it an evidence of a failed looting process on the ancient site?

- There is a complete lack of documentation of the excavation and the artifact’s transfer history, which was shared unequally by the three museums. I’m quite sure that the Iraqi Museum in Baghdad has at least some information. In the midst of the current chaos incurred by the 2003 war and its aftermath, it is difficult to trace back much further than that.

- The content of the reliefs definitely cannot be compared with their counterparts, which are housed in various museums around the world, e.g., the British Museum. The fragments are relatively small and do not convey any clear-cut and complete scene. On the contrary, they show part of a body of an apkallu or a scared tree. Two of them have nothing but the “standard inscription” of Ashurnasirpal II. The records show that Sir Henry Layard cut and threw out many parts of the reliefs, before sending them out to England, in order lighten the carry load.

- The fragments may be part of fragments that were left behind by one or more prior excavating team(s) for some reason or another. On the other hand, it may be that the excavators just wanted to pick up, transfer, and conserve anything on the spot with no intention to display them or research further.

- The Sulaymaniyah Museum has done conservation work and displayed one fragment only. It lies in one of the halls, which houses several masterpieces of the museum; this hall was renovated by UNESCO in 2013. Thi relief was not on display before then. The museum has no intention to conserve, display, and study the other seven reliefs.

- The Sulaymaniyah Museum is on the list of museums, which houses wall reliefs from the northwest palace at Nimrud.

My intention to take photos of these reliefs and to publish them via Ancient History Encyclopedia (AHE) is to document their presence and share them with the world. Even among Iraqis, including those involved in archaeology or history, many and many have not heard about these reliefs of the Sulaymaniyah Museum.

I’m very grateful to Mr. Hashim Hama Abdullah, Director of the Sulaymaniyah Museum for his continuous and unlimited help. A special gratitude goes to Mr. Mutasim Rasheed Abdulrahman, also known as Shex Mutasim (Arabic معتصم رشيد عبد الرحمن, المعروف بشيخ معتصم) for his cooperation; without his kind help, this article would have not been published. Mr. Mutasim is a well-known archaeologist in Iraq. He conducted several excavations on many ancient sites across Iraq. His role as an acting director of the Sulaymaniyah Museum was vital and central in the development and expansion of the museum. Because of his political views, he was harassed and ignored by subsequent governments. Currently, he is retired and lives happily in a rural house.

In the words of the British author Margaret Drabble, “When nothing is sure, everything is possible.” Enjoy these photos of the reliefs!

Wall relief from the northwest palace of Ashurnasirpal II. This fragment shows the right hand of an Apkallu (sage or protective spirit) holding a bucket before branches of the “sacred tree” or “the tree of life.” Part of the “standard inscription” of Ashurnasirpal II also appears at the upper part. A portion of a fringed robe appears on the thigh (extreme left). This fragment was the only one among all other wall reliefs to undergo conservative work. It is on display within one the halls of the Museum. From Nimrud, Northern Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq. The Sulaymaniyah Museum, Iraqi Kurdistan. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

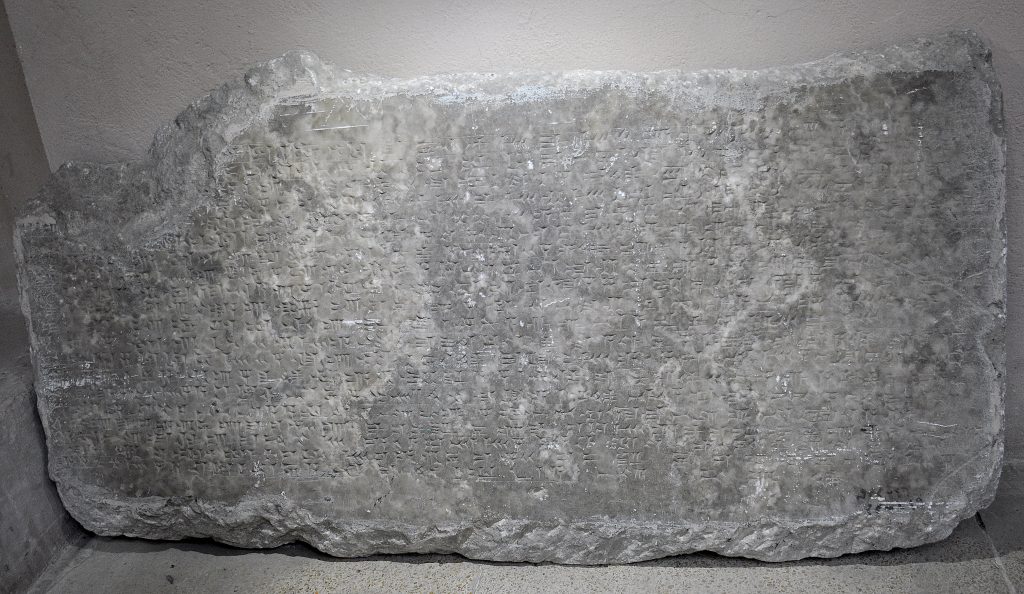

Fragment of a wall relief from the northwest palace of Ashurnasirpal II. What has survived is part of the torso of an Apkallu. He wears a fringed robe. There is a bracelet on his left wrist, as well as an armlet at the upper left arm. His hand holds a bucket (extreme left). Note the musculature of the forearm. There is a armlet at the raised upper right arm; he seems to hold a cone (not shown). The “standard inscription” of Ashurnasirpal II runs horizontally on the lower part. The fragment appears to be cut out non-perpendicularly; therefore, the scene appears somewhat oblique. From Nimrud, Northern Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq. Not on display. Exclusive photo; never-before-published. The Sulaymaniyah Museum, Iraqi Kurdistan. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

This fragment was labeled, at the left upper part, in Arabic: “م م ق 380,” which means “Mosul Museum 380.” Note the “horizontal slit” at the upper margin, which seems to be caused by an electric abrasive saw during the cutting process of the relief. The relief shows part of the lower legs of two figures, barefooted. It is not credible that the King is shown barefooted; moreover, it is not clear whether those figures were Assyrian attendants or Apkallu. They wear long fringed robe, exquisitely carved. It is unknown whether this fragment came from the northwest palace or from another palace within Nimrud, or from another Assyrian palace in Nineveh or Dur-Sharrukin. Not on display. From northern Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq. Exclusive photo; never-before-published. The Sulaymaniyah Museum, Iraqi Kurdistan. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

This detail of a large wall relief from Nimrud shows the lower part of the fringed robe wore by an eagle-headed protective spirit (Apkallu). His foot is bare. Compare this image with the similar image above, at the Sulaymaniyah Museum. However, the robe is different, and this Apkallu stands between two “sacred trees”; there is no body before or behind him. From the northwest palace at Nimrud, Room I. Northern Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq. Assyrian, 865-860 BCE. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

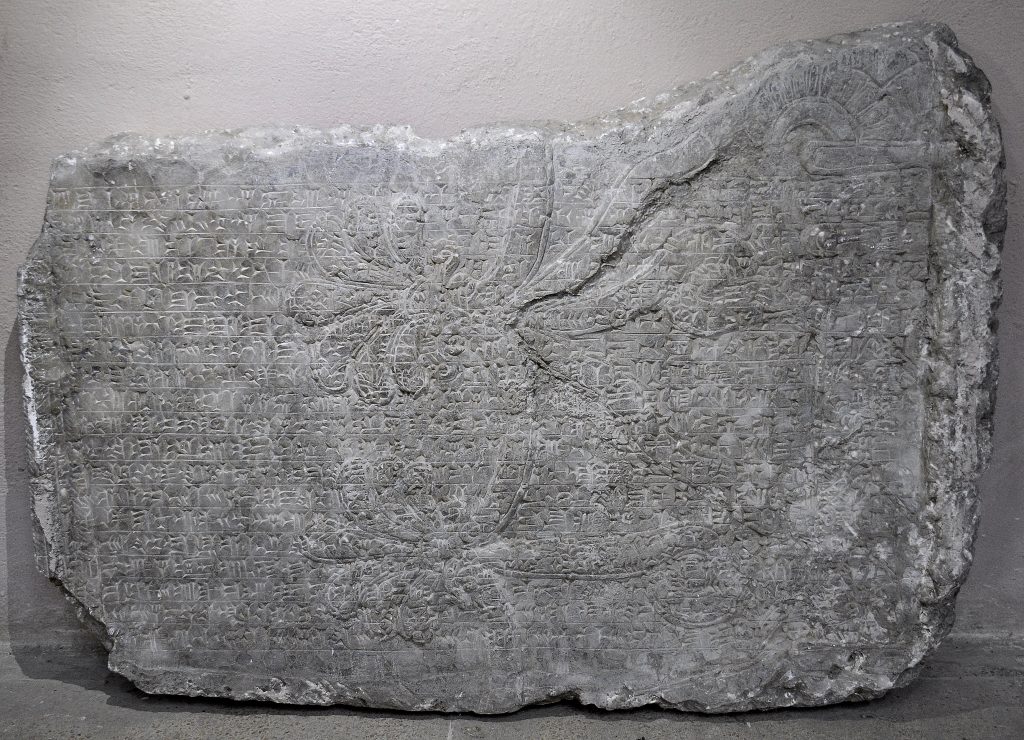

Fragment of a wall relief from the northwest palace of Ashurnasirpal II at Nimrud. The “standard inscription” of Ashurnasirpal II runs over the left half of the “sacred tree” or “tree of life”; sadly, the right half is lost. The right part of the upper margin was cut out in a way to preserve part of the “sacred tree”; therefore, that margin appears non-horizontal. From Nimrud, Northern Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq. Not on display. Exclusive photo; never-before-published. The Sulaymaniyah Museum, Iraqi Kurdistan. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

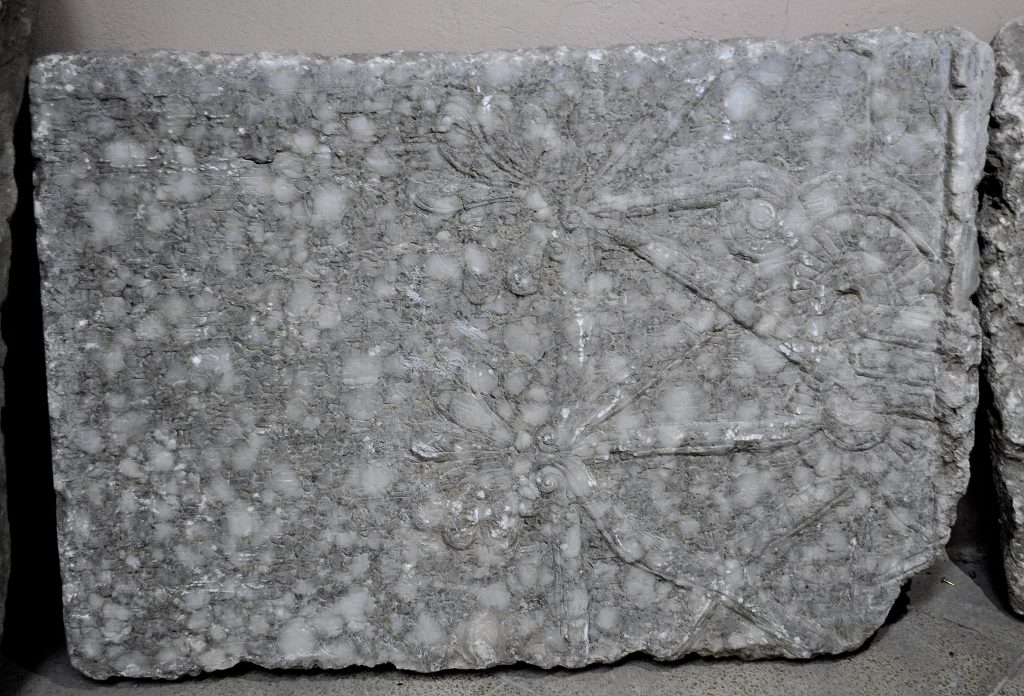

This fragment of a wall relief from the northwest palace of Ashurnasirpal II at Nimrud shows parts of the “sacred tree” or “tree of life.” The tree is overshadowed by the “standard inscription” of Ashurnasirpal II. Not on display. From Nimrud, Northern Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq. Exclusive photo; never-before-published. The Sulaymaniyah Museum, Iraqi Kurdistan. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

A fragment of a wall relief from the northwest palace of Ashurnasirpal II at Nimrud. The “standard inscription” of Ashurnasirpal II runs over part of a “sacred tree” or “tree of life.” From Nimrud, Northern Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq. Not on display. Exclusive photo; never-before-published. The Sulaymaniyah Museum, Iraqi Kurdistan. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

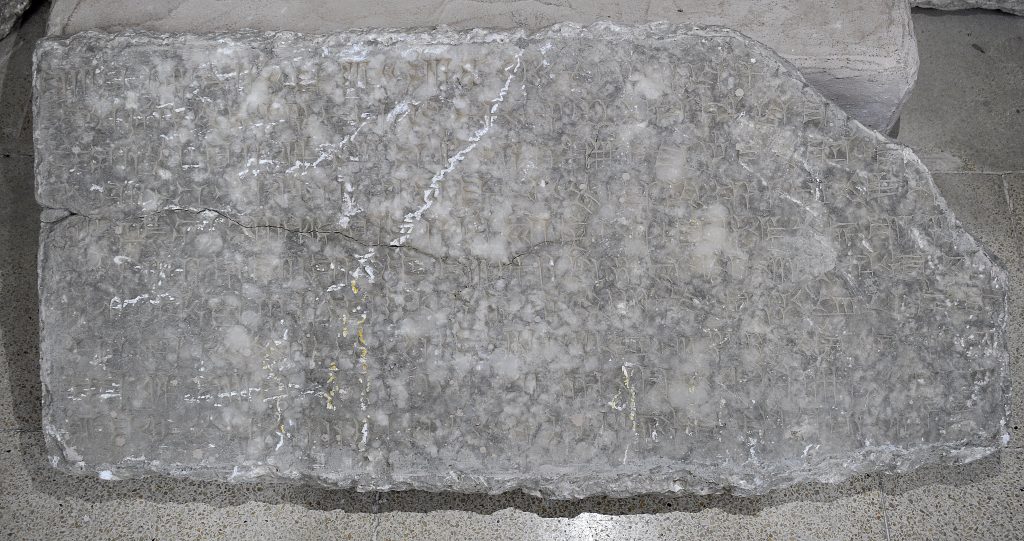

This fragment does not depict any scene or figure. The “standard inscription” of Ashurnasirpal II is the only content, filling out all of the surface of the relief’s fragment. The cuneiform inscriptions are clear. Note the label at the right lower angle. It reads in Arabic language: “م م ق 46”; this is translated as “Mosul Museum 46.” The other label below it is worn out. From Nimrud, Northern Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq. Not on display. Exclusive photo; never-before-published. The Sulaymaniyah Museum, Iraqi Kurdistan. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

This fragment is similar to the previous one; it contains only the “standard inscription” of Ashurnasirpal II. From the northwest palace at Nimrud, Northern Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq. Not on display. Exclusive photo; never-before-published. The Sulaymaniyah Museum, Iraqi Kurdistan. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

This large wall relief summarizes what we have seen in the aforementioned reliefs at the Sulaymaniyah Museum. An eagle-headed and winged man (Apkallu, Sage, or protective spirit) stands in the middle of the panel and is flanked by two “sacred trees.” He wears a long fringed and exquisitely carved robe. There are bracelets (which differ from the Sulaymaniyah Museum ones) and armlets. The anatomy of the muscles of the arms and legs were accentuated, conveying a message that he is a powerful creature. His left hand holds a bucket while the right one holds a cone. He is not bare-footed; he wears sandals. The “standard inscription” of Ashurnasirpal II runs horizontally across the panel. This is part of a ceremonial religious rite. From the northwest Palace at Nimrud, Room F, panel 8. Northern Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq. Assyrian, 865-860 BCE. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Disclaimer

Sulaymaniyah, Iraq is presently a part of Iraqi Kurdistan (or “Kurdistan Region” or “Southern Kurdistan”). All of these terms are used to describe the region. Neither the author nor Ancient History Encyclopedia (AHE) endorses any specific of the aforementioned terms.