In the heart of southern England, the city of Bath emerges from the countryside with picturesque stone buildings and neoclassical Georgian architecture. I recently visited the city’s Roman baths, which were built nearly two millennia ago and continue to impress over a million visitors each year.

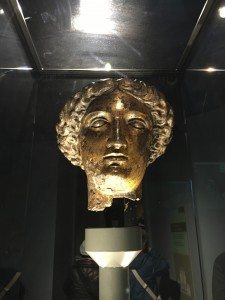

The Romans settled at Bath in the first century on the site of a pre-existing British temple to the Celtic goddess Sulis, whom the Romans identified with their own Minerva. The Romans named it Aquae Sulis – the waters of the goddess Sulis, in an attempt to appease the local Britons. To the polytheistic Romans, belief in a god or goddess was not exclusive – the Celtic goddess Sulis was roughly equivalent the Roman goddess Minerva (Athena in Greece), so they worshipped the goddess at the spa as “Sulis Minerva.” Unlike most Roman settlements in Britain at the time, which were garrisons for military occupation, Aquae Sulis was intended to be a place of relaxation centered on the bath complex.

The goddess Sulis Minerva, worshipped at the temple near the baths. Image © Caroline Cervera.

Bath is located on a natural geothermal spring that has made it important to residents throughout history. Water makes a long journey to reach the spring, beginning as rainfall in hills to the south, then being absorbed into limestone aquifers underground, and eventually traveling deep into the earth, where it is heated by the planet’s geothermal energy. It rises to the surface at Bath at a rate of 1,170,000 liters (257,364 gallons) per day and a temperature of 46 degrees Celsius (115 degrees Fahrenheit).

Water flows through the original stone structure. Image © Caroline Cervera.

I paid a visit to the baths on a brisk day in March. Their entrance blends seamlessly into the modern town, most of which was built during the Georgian period to emulate the original Roman buildings. By design, all of the city’s buildings are made of the same local limestone, the aptly-named “Bath stone,” giving it a quaint charm that attracts many visitors. In the pedestrian shopping district, people weave in and out of Ionic columns that mark the entrance to the baths, providing an interesting juxtaposition of ancient and modern that came to characterize the rest of my experience at Bath.

People gather near the entrance to the baths. Image © Caroline Cervera.

The Great Bath

Inside, I found the baths as they were restored during the Victorian era. A neoclassical-style superstructure allowed me to get a bird’s eye view of the water from above. The baths are set about half a story below the ground, so the upper platform is surprisingly close to ground level outside the complex, but it stands a solid story above the Great Bath’s green water.

Mist rises from the water in the Great Bath. Image © Caroline Cervera.

It was even hazier inside the baths than it was on that cloudy day, due to steam rising from the warm water. It only added to the mystical atmosphere that came from standing at the same spring that the ancients deemed so sacred.

The city’s pride in its heritage shows throughout the Great Bath area. Although the superstructure was made in the 19th century, it looked and felt ancient itself. The designers even included a number of statues of Roman emperors along the walkway which have unfortunately been damaged by acid rain.

A row of statues of Roman emperors. Image © Caroline Cervera.

Image © Caroline Cervera.

The Roman Baths

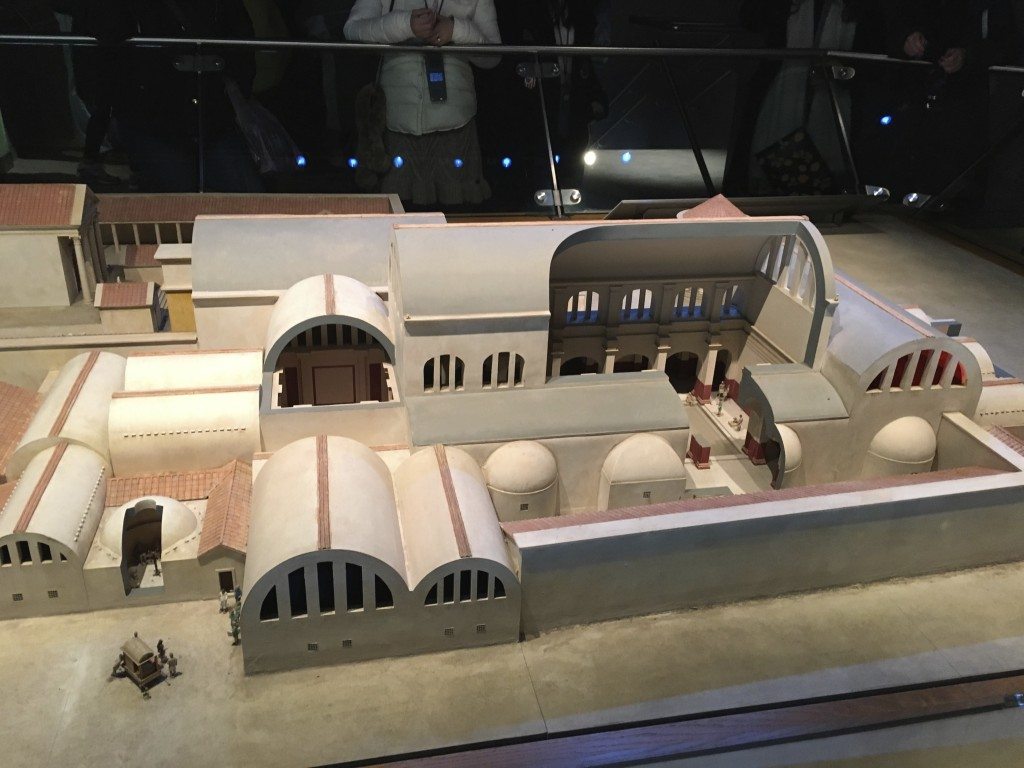

During their heyday, the baths would have looked something like this model. They included a number of pools of varying temperatures. Romans would have first bathed in the warm pool (tepidarium, with the same root as our word “tepid”), followed by the hot pool (caldarium), then finally the refreshing cold bath (frigidarium). If they chose, they could complete their visit with a swim in the Great Bath, pictured here.

Image © Caroline Cervera.

Invented by the Greeks and perfected by the Romans, the hypocaust was one of the most remarkable technologies included in the bathing complexes. By placing a floor on stacks of tiles, the Romans created a space for air to flow beneath the floor. When they connected this space to a furnace and pumped hot air into it, it heated the floor, and in this case, the water that stood above it, allowing them to have a variety of water temperatures in the different baths. The stacks of tiles from beneath the floors still remain here and at other sites across the Roman world.

Remnants of the hypocaust. Image © Caroline Cervera.

The actual Roman temple to Sulis Minerva at the complex does not survive, but a few pieces of its pediment have been recovered. It would have featured this fierce-looking face of a Gorgon, a mythological creature, looking down at visitors from a height of 49 feet (15 meters). The museum uses a projection to show how these pieces would have fit into the rest of the pediment.

The Gorgon and how it would have fit into the original pediment. Image © Nick Peel.

Although they are remarkable feats of architecture and engineering, the baths also showed me more of the human side of history through artifacts and human remains.

The Celtic People of Aquae Sulis

Here I came face to face with one of the residents of ancient Aquae Sulis, a 45 year old man whose remains were found nearby.

Image © Caroline Cervera.

My favorite object in the museum was a plaque thought to be a portrayal of three Celtic mother-goddesses. The Celtic portrayal of the human form is so different from the Roman style that you can almost forgive the ancient alien theorists based on the looks of this relief.

Image © Caroline Cervera.

People went to the baths not only to bathe, but also to socialize. However, with social interaction, there come opportunities for crime. These are lead curse-tablets (defixiones) that were etched with a curse and thrown into the water to ask the goddess to curse someone on the writer’s behalf. I had a good laugh when I learned that many of them were written to curse those who stole bathers’ clothes while they swam!

Lead curse tablets that were thrown into the baths. Image © Caroline Cervera.

An amusing sampling of the curses:

“Docimedis has lost two gloves and asks that the thief responsible should lose their minds and eyes in the goddess’ temple.”

“”May he who carried off Vilbia (a woman) from me become liquid as the water. May she who so obscenely devoured her become dumb.”

About a stolen ring: ‘…so long as someone, whether slave or free, keeps silent or knows anything about it, he may be accursed in (his) blood, and eyes and every limb and even have all (his) intestines quite eaten away if he has stolen the ring or been privy (to the theft).’

Another curse tablet – perhaps the most ominous of the set – only contained a list of names.

It was fascinating to see how humans thousands of years ago share some of the same struggles we face today: theft, vengeance, and stolen lovers. Great monuments and buildings can provide one aspect of history, but everyday objects used by ancient people provide another invaluable side of the past that I was delighted to see at the Roman baths.