One of the most important discoveries in marine archaeological history occurred in 1998, just off Indonesia’s Belitung Island in the western Java Sea: A 1,200-year-old Arabian dhow with an astounding cargo of gold, silver, ceramic artifacts, coins, and tangible personal effects. The ship’s hold contained some 57,000 pieces in total and yet no human remains. The Lost Dhow: A Discovery from the Maritime Silk Route, now on show at the newly opened Aga Khan Museum in Toronto, Canada, explores the movement of cross-cultural exchange, trade, and technology between the Abbasid Caliphate (750-1258 CE) and Tang dynasty China (618-907 CE) through the prism of an ancient shipwreck. In this exclusive interview, James Blake Wiener of Ancient History Encyclopedia (AHE) speaks to Mr. John Vollmer, Guest Curator for the Aga Khan Museum’s presentation of this exhibition, about the importance of the objects in this exhibition and what the exhibition means to the recently opened museum.

In this exclusive interview, James Blake Wiener of Ancient History Encyclopedia (AHE) speaks to Mr. John Vollmer, Guest Curator for the Aga Khan Museum’s presentation of this exhibition, about the importance of the objects in this exhibition and what the exhibition means to the recently opened museum.

JW: John Vollmer, welcome to Ancient History Encyclopedia, and thank you so much for speaking to me about this fantastic presentation of 300 artifacts at the Aga Khan Museum.

The Lost Dhow was a popular show at the Asian Civilisations Museum of Singapore; now, as the show makes its North American debut, how important was it for the Aga Khan Museum to host this exhibition?

JV: As I see it, there are at least three reasons why it is important for us.

First, it fulfills the Museum’s mission of offering visitors windows into worlds unknown or unfamiliar, by shedding light on the artistic, intellectual and scientific heritage of Muslim civilizations and their contributions in an interconnected global and world heritage. In this case, those windows focus on global commerce in the Indian Ocean region during the ninth century CE and highlight the role that Muslim cultures played in those exchanges.

Secondly, on a strategic level, this is a demonstration of a brand new museum’s positioning within the world’s museum community. It highlights the Aga Khan Museum’s significance locally and burnishes its reputation internationally. It is also a clear demonstration of the leadership role that the Museum is determined to play in exposing its visitors and online audiences to the impact of Muslim civilizations in diverse ways.

Thirdly, although less obvious to visitors, is the Museum’s resolve to engage the academic and scientific communities in dialogue about wide-ranging issues affecting maritime archaeology, recovery, conservation, the art market, and the roles museums play in this world. As you know, this exhibition was initially a joint project between the Asian Civilisations Museum and the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. When controversy arose about the archaeological standards employed in the recovery of the cargo, the Smithsonian cancelled its plans to host the exhibition. The issues surrounding the controversy over the Belitung shipwreck are complex and nuanced and have been raised and discussed in a wide range of programs at the Museum, including an upcoming international symposium (February 28, 2015) that centers on this exhibition.

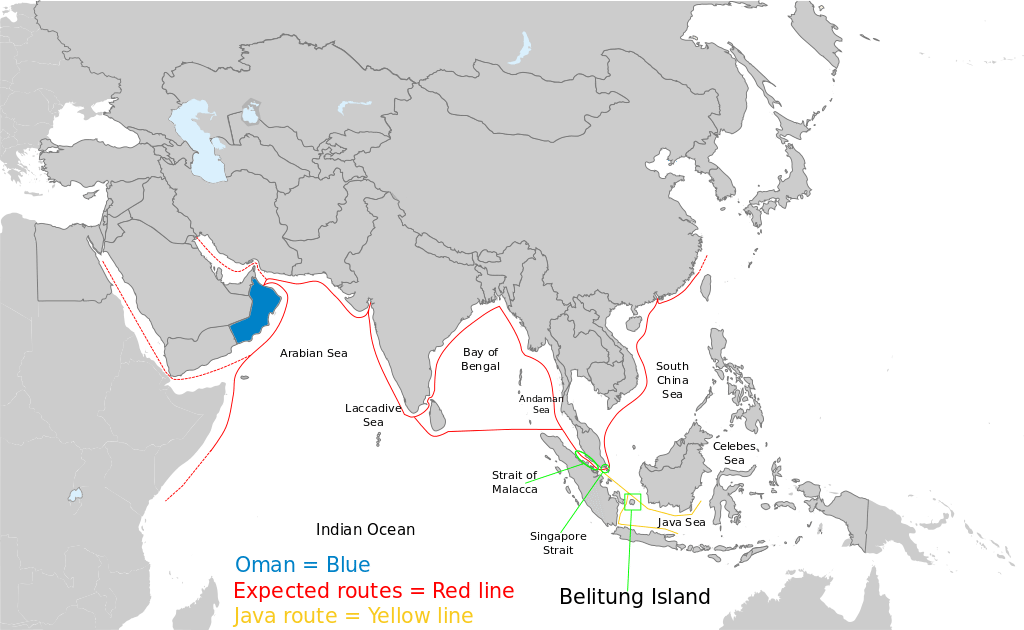

Map of the Middle East and Asia showing maritime trading routes and geographic places of interest. (Modern borders are demarcated.)

JW: Could you perhaps explain to our readers what the “Maritime Silk Route” was and contextualize this fascinating discovery in relation to our understanding of maritime trade in Late Antiquity (or the Early Middle Ages)? Should we think of the Maritime Silk Road as the watery half of the world economy in the eighth and ninth centuries CE?

JV: Since the Neolithic Revolution that transformed society from hunters and gatherers into farmers and herders over 1,200 years ago, commerce has been part of the universal human condition. A challenge in facilitating the exchange of goods and services for items and materials that are not locally available is, and has always been, transport. Domesticated pack animals increased the payload significantly; sleds and carts offered even greater returns but required roads and bridges to be effective. Boats and ships further revolutionized trade, increasing volume exponentially.

The Indian Ocean washes the shores of the civilizations of East Africa, West Asia, the Indian Subcontinent, Southeast Asia, and East Asia. While skirting the shorelines of these waters certainly connected local ports from very early times, the discovery that the seasonal monsoon winds could be harnessed for open ocean sailing by Arab traders during the first century of the current era transformed commerce into a truly global phenomenon. Notwithstanding the threats posed by weather, faulty equipment, or piracy, maritime trade on this global scale required a reliable and functioning network of ports and shipping facilities. In addition, trade required that people engage in the myriad of tasks involved in placing orders, securing goods, handling, packing, storing, repacking, transporting cargos from ports, and distributing them to markets.

The existence of powerful empires in East and West Asia — as well as in Southeast Asia and the southern parts of the Indian subcontinent — contributed to stability in the region and encouraged trade to flourish. When you consider the estimated weight of the cargo of the single vessel we know as the Belitung shipwreck at 25 tons and compare it to the mere 300 to 400 pounds a camel making the overland trek could manage, you begin to appreciate the scale of the “watery half” of the world economy at this period.

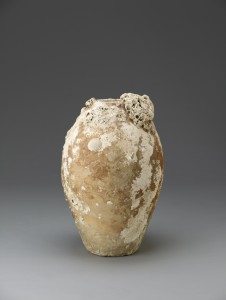

Large Packing Jar. Guangdong Province, China, 825-50 CE. Acc. No. 2005.1.52956. Copyright © Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore. Photo by John Tsantes and Robert Harrell, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery.

JW: The vast majority of the 60,000 items recovered from the dhow wreck were the tens of thousands of Changsha bowls — why was this the case? Aside from being coveted by wealthy elites in the Iraqi cities of Basra and Baghdad, what is remarkable about these ceramics?

JV: As we worked on this exhibition, the team often joked about the supply of dishes for a chain of Chinese restaurants across the Indian Ocean region. It is a completely frivolous notion — except broken pieces of these Changsha ceramics have been found in excavations from the coast of eastern Africa to Indonesia. They are a testament both to China’s capacity for mass manufacturing and to foreign demands for its goods.

China’s ninth-century CE mass production was on a scale not seen in Europe before the 16th century CE. Much like today’s Chinese table ceramics, which run the gambit from inexpensive to pricey, supplying the lower end of the market supports the upper end by creating demand, distinguishing taste, and celebrating rarity. What we do not know is who actually acquired and used the small bowls that were so widely distributed across the region. Certainly they would have been more expensive than locally manufactured dishes, but the sheer volume of the Changsha wares, if we extrapolate from the Belitung cargo, suggests a broad range of people found them desirable and could afford them. Merchants knew they would sell, or there would not have been such a huge order on board this dhow.

JW: How does The Lost Dhow illustrate the brilliant and creative set of exchanges between China and the Islamic world over a millennium ago, Mr.Vollmer? Tang China and the Abbasid Empire were locked in a complex embrace of trade and competition around 800 CE; both regarded Central Asia as their backyard, and yet both were dependent on global trade.

JV: Engagement between these empires took many forms: warfare, diplomacy, and commerce, as well as artistic and technological exchange. Foreigners involved in international trade lived and worked in the port cities throughout the region. Language, religious practices, dress, cuisine, and different ways of doing things flowed outward from these communities.

Among the most humble objects recovered from the shipwreck are personal items that have been associated with the crew on board. Gaming pieces, a portable ink stone, a cymbal, spoons, a mortar and pestle, a glass vial — these have been clustered by culture in the exhibition to represent South Asians, Chinese and West Asians. From other records we know that Arabs, Iranians, Omanis, Chinese, Malays, Indians, Sri Lankans, Thais, Javanese, and Somalis, among others were involved in ninth-century CE trade.

Cast Gold Cup with Chased Decorations. China, 825-50 CE. Acc. No. 2005.1.00918. Copyright © Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore. Photo by John Tsantes and Robert Harrell, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery.

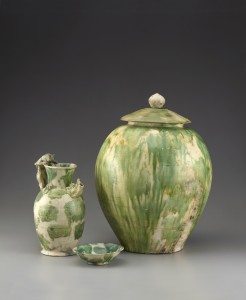

Traders and suppliers of the period were well-informed about the tastes and demands of foreign markets. A group of bright green-splashed white wares in the shipment is related to the two- and three-color splashed wares used in China; but these single-color wares were made only for export to the Abbasid Empire.

Two of the three underglaze-painted, cobalt-decorated, white wares found in the wreck are the earliest Chinese experiments to produce the ubiquitous blue-and-white ceramics we call “China.” Cobalt ore is found only in Iran. It and the technology of using it as pigment to decorate ceramics were imported from West Asia. Using blue cobalt to decorate the much-coveted Chinese pure white high-fired stonewares with patterns of lozenges with palmettes at the corners — a motif favored by the Abbasids — sheds light on some of the complexities of exchange beyond the fiscal one.

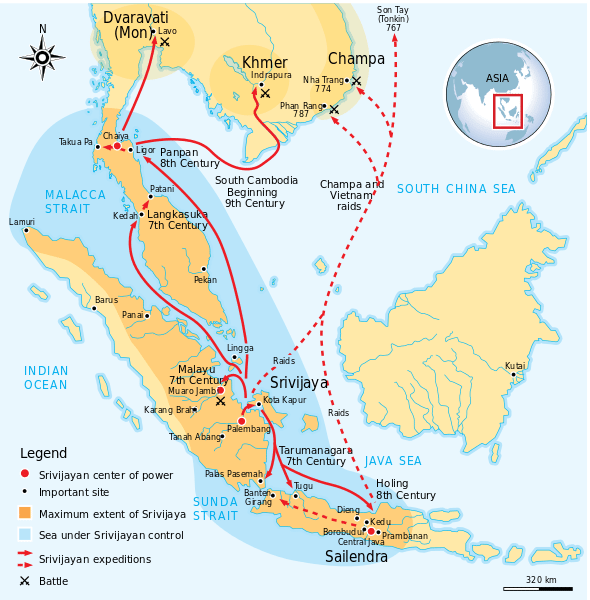

JW: Special mention ought to be made of the Buddhist kingdom of Srivijaya, which was based in Sumatra and Java and located in present-day Indonesia. It, too, was at the crossroads of the global maritime trade. In ways similar to present-day Singapore, it controlled the main choke point of that trade — the Straits of Malacca — with a monopoly on the movement of spices that were worth more per ounce than gold at that time: nutmeg, clove, and cinnamon.

Some scholars theorize that this 17-meter dhow was actually on its way to Java or Sumatra before sailing towards Arabia, as Belitung Island is not on the way to Malacca. What evidence is there to further this assertion?

Could the cargo have even been an imperial diplomatic gift, perhaps to the caliph in Baghdad? What do you believe?

Maximum extent of Srivijaya Empire around the eighth century CE. The empire included parts of Sumatra, Central Java, and the Malay Peninsula. The red arrows show a series of Srivijayan military campaigns or naval raids.

JV: I believe international commerce then, as now, is much more complicated than taking a single cargo from point A to point B. Indeed, this is true, despite our 20th-century “invention” of containerized shipping, which has transformed modern global maritime commerce. The merchants involved with our dhow were already practicing this concept in the mid-ninth century CE. Large ceramic jars filled with stacked bowls made for easy loading and unloading and could facilitate distribution at any number of ports of call. Chinese utilitarian ceramics (the bulk of the surviving cargo) were marketable everywhere in the Indian Ocean region and may well have been used to exchange for other commodities at many ports. For a West Asian vessel (which we know because of its particular sewn plank construction) to return to the Persian Gulf region without spices — some of the most valuable of all trade goods — is incomprehensible.

The presence of luxury wares of gold and silver reflecting the most sophisticated Chinese Tang dynasty court tastes or the “collection” of antique Chinese copper alloy mirrors suggests a much more focused purpose for the shipload. Simon Worrall, who has written the catalogue that accompanies the exhibition, has speculated that these goods, many of which are decorated with traditional Chinese wedding symbols, were part of a dowry for a royal wedding. We have no record of a Tang princess being sent West, nonetheless these pieces are truly wonderful, and powerfully enigmatic. They have a story to tell, which at this point we are unable to discern.

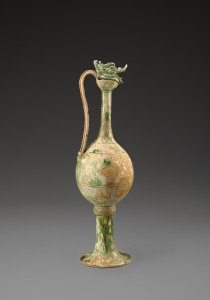

Monumental Ewer with Dragon Top. Probably Gongxing kilns, Henan Province, China, 825-50 CE. Acc. No. 2005.1.00900-1/2–2/2. Copyright © Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore. Photo by John Tsantes and Robert Harrell, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery.

JW: Mr. Vollmer, what surprises await visitors to The Lost Dhow? Are there any artifacts that are not to be missed? If so, which in particular?

JV: Among the gold and silver objects is a solid gold cup, which was made in China, but reflects technological, iconographic, and stylistic influence from West and Central Asia. With its decoration of exotic dancers and musicians and a thumb guard with addorsed heads of bearded Central Asians, it literally gleams in the gallery. It is significantly larger than any other gold cup found in China — this example is mug-sized; those from Chinese tombs tend toward the demitasse range. Was this a personal trophy? A special order destined for trade or gifting? We simply do not know.

I have mentioned the blue-and-white dishes, but a visitor should not miss the charming green-splashed cups and goblets with three-dimensional fish or turtles at the bottom that would have been revealed when the beverage was drunk, or the handle of a ewer that is a cleverly sculpted lion, which literally bites the rim of the jug.

The Changsha bowls that make up over half the exhibition have designs in two colors of underglaze painting. There are a limited number of stock designs, which are repeated over and over by hand, probably by many artisans. I like the fact that no two of the same pattern are identical. I also adore the small selection of Changsha bowls with what we call “eccentric” designs: one is signed with rather pompous lineage, one bears a caricature of a curly-headed bearded foreigner, and another has been used by its painter to practice writing Chinese characters.

While the majority of ceramics are proportioned for table use, a green-splashed white ware ewer with a dragon-headed stopper stands over a meter high. The shape is based on West Asian metalwork prototypes, but at this scale it must have been made for show, not use.

Green-Splashed Ewer, Bowl and Lidded Jar. Probably Gongxing kilns, Henan Province, China, 825-50 CE. Acc. Nos. 2005.1.00403, .00398, and .00377-1/2–2/2. Copyright © Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore. Photo by John Tsantes and Robert Harrell, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery.

I have also mentioned the large ceramic containers that were used to hold Changsha bowls. A number of monumental functional jars and containers used for water and food for the crew, as well as container for other trade goods, have a singular majesty. Some still bear witness to the nearly 1,200 years they were lost to human memory at the bottom of a West Java Sea where a coral reef gradually engulfed the stern area of the sunken vessel.

JW: Finally, what was the most rewarding part of working on The Lost Dhow?

JV: I have worked with Chinese art for most of my career and have handled Tang dynasty ceramics in several museums and private collections. To this point they had always been singular, precious objects. The Belitung shipwreck demanded that I (and the visitors to the exhibition) acknowledge that in their own time these artifacts were really commodities, produced in large numbers, regardless of how exquisitely each has been realized. For the merchants involved with this cargo, these wares had values calculated in monetary terms.

I also loved teasing out the threads of a complex narrative from this shipwrecked dhow and enjoyed working with a fantastic team of designers, educators, curators, and installation technicians to produce this exhibition. The display conveys to our visitors the physicality of the ship — its size and specifications — and highlights its dazzling cargo.

Blue-and-White Dish. Gongxing kilns, Henan Province, China, 825-50 CE. Acc. No. 2005.1.00474. Copyright © Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore. Photo by John Tsantes and Robert Harrell, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery.

JW: Mr. Vollmer, thank you for speaking with me and sharing your knowledge. We eagerly await the next exhibition at the Aga Khan Museum.

JV: Thank you. I appreciate your questions and this opportunity to talk about The Lost Dhow.

Although I am not involved in the next show, a pair of exhibitions: Visions of Mughal India: The Collection of Howard Hodgkin and Inspired by India: Paintings by Howard Hodgkin, opening in February 2015. The lifelong fascination with India by British artist Howard Hodgkins (1932-) will, I am sure, open other windows for Aga Khan Museum visitors.

The Lost Dhow: A Discovery from the Maritime Silk Route is on display at the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto, Canada until April 26, 2015. A richly illustrated publication, Tang Treasures and Monsoon Winds, written by Simon Worrall and published by the Aga Khan Museum, accompanies the exhibition.

- A photograph on an Arabian dhow in Sur, Oman. Original uploader was Ji-Elle at en.wikipedia, 2011-20-01. (Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts.)

- Map of the Middle East and Asia showing maritime trading routes and geographic places of interest. (Modern borders are demarcated.). Original uploader was Asie.svg: historicair at en.wikipedia, 2006-20-11. Modifications made by Chaosdruid, 2011-14-08. (This work has been released into the public domain by its author, Asie.svg: historicair at the wikipedia project. This applies worldwide.)

- Large Packing Jar. Guangdong Province, China, 825-50 CE. Acc. No. 2005.1.52956. Copyright © Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore. Photo by John Tsantes and Robert Harrell, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery.

- Cast Gold Cup with Chased Decorations. China, 825-50 CE. Acc. No. 2005.1.00918. Copyright © Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore. Photo by John Tsantes and Robert Harrell, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery.

- Maximum extent of Srivijaya Empire around the eighth century CE. Expanding from Sumatra, Central Java, to Malay Peninsula. The red arrows show the series of Srivijayan expedition and conquest, in diplomatic alliances, military campaign, or naval raids. Original uploader was Gunawan Kartapranata at en.wikipedia, 2009-27-08. (This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.)

- Monumental Ewer with Dragon Top. Probably Gongxing kilns, Henan Province, China, 825-50 CE. Acc. No. 2005.1.00900-1/2–2/2. Copyright © Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore. Photo by John Tsantes and Robert Harrell, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery.

- Green-Splashed Ewer, Bowl and Lidded Jar. Probably Gongxing kilns, Henan Province, China, 825-50 CE. Acc. Nos. 2005.1.00403, .00398, and .00377-1/2–2/2. Copyright © Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore. Photo by John Tsantes and Robert Harrell, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery.

- Blue-and-White Dish. Gongxing kilns, Henan Province, China, 825-50 CE. Acc. No. 2005.1.00474. Copyright © Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore. Photo by John Tsantes and Robert Harrell, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery.

John Vollmer, Guest Curator for the Aga Khan Museum’s presentation of this exhibition, is an independent curator and scholar specializing in Asian art, textiles, decorative arts, and design. He is a former director of the Design Exchange in Toronto and Kent State University Museum in Ohio. He was Senior Curator of Fine and Decorative Arts at the Glenbow Museum, Calgary and has held curatorial positions in the Far Eastern Department and the Textile Department at the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto. Vollmer is President of Vollmer Cultural Consultants Inc., based in New York City.

All images featured in this interview have been attributed to their respective owners. Images lent to the Ancient History Encyclopedia by the Aga Khan Museum and Mr. John Vollmer have been done so as a courtesy for the purposes of this interview and are copyrighted. (Copyright © Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore. Photo by John Tsantes and Robert Harrell, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery.) Unauthorized reproduction prohibited. A heartfelt thank you is extended to Ms. Ms. Jackie Koffman, Publicist at Holmes PR, for helping arrange this interview. Special thanks is also extended to Ms. Karen Barrett-Wilt, who assisted in the editorial process. The views presented here are not necessarily those of the Ancient History Encyclopedia. All rights reserved. © AHE 2015. Please contact us for rights to republication.