Winged Isis pectoral 538–519 B.C. Gold. Harvard University—Boston Museum of Fine Arts Expedition. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Located at the intersection of long distance trade between East Africa, the ancient Near East, and the classical world, ancient Nubia was Egypt’s rich and powerful neighbor to the South. Successive Nubian cultures dominated what is modern-day Sudan and southern Egypt for over two millennia, developing in turn a distinctive set of cultural aesthetics and an impressive level of craftsmanship. Gold and the Gods: Jewels of Ancient Nubia, a new exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, entices visitors with 95 items on display, including jewels, gems, and exquisite artifacts of personal adornment.

String of beads with a glazed quartz pendant 1700–1550 B.C. Faience, glazed quartz. Harvard University—Boston Museum of Fine Arts Expedition. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

In this exclusive interview, James Blake Wiener of Ancient History Encyclopedia (AHE) speaks to Ms. Denise Doxey, Curator of Ancient Egyptian, Nubian, and Near Eastern Art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, about the history, artistry, and splendor of ancient Nubian jewelry.

JW: Curator Denise Doxey, thank you for speaking to Ancient History Encyclopedia (AHE) about Gold and the Gods: Jewels of Ancient Nubia at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston! I am delighted that you have chosen to share your expertise and insight with us.

I wondered if you might tell us more about the Museum’s outstanding collection of jewelry from ancient Nubia. It should be noted that the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston is the only museum in the United States able to mount an exhibition devoted solely to Nubian jewels, drawing exclusively from its own collection. How was this collection amassed, and what led to the organization of this exhibition?

Necklace with cylinder amulet case 1700–1550 B.C. Silver, glazed crystal, carnelian, and faience. Harvard University—Boston Museum of Fine Arts Expedition. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

DD: Thank you, James. It is a pleasure to discuss the exhibition with you. But I should point out that much of the information I will be sharing is the result of research by my colleague and co-curator of the exhibit, Yvonne Markowitz, who just retired as the MFA’s Rita J. Kaplan and Susan B. Kaplan Curator of Jewelry. She really took the lead on the jewelry scholarship, while I handled the history and archaeology; we have her to thank for the exhibit coming to pass. She began her career at the MFA working with Nubian jewelry and has long wanted to do an exhibit featuring it. We had to take advantage of her expertise before she retired!

You are correct that we are the only museum that could mount an exhibit like this one exclusively from our own collection, not only in the US but anywhere outside Sudan. The MFA, in conjunction with Harvard University, carried out excavations in northern Sudan between 1913 and 1932. Our Curator of Egyptian Art, George Reisner, who was also a professor at Harvard, led the expedition. Prior to Reisner’s discoveries, ancient Kushite or “Nubian civilization” was completely unknown. He could not have fully comprehended the importance of what he had found. Among the sites the expedition excavated were Kushite royal and elite cemeteries at Kerma, el-Kurru, Nuri, Gebel Barkal and Meroe, and a series of ancient Egyptian fortresses in Nubia. The policy of the Sudanese government, at the time, was to divide finds with the excavators, giving the MFA a collection unparalleled outside Khartoum. Everything in the exhibition comes from the excavations.

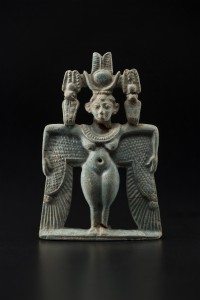

Winged goddess pectoral 743–712 B.C. Faience. Harvard University—Boston Museum of Fine Arts Expedition. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Another fact worth noting is that in addition to the objects themselves, the MFA holds all of Reisner’s excavation records, including field notebooks, object registers, photo registers, and glass plate negatives. Reisner was a pioneer in using photography to record his finds while they were still in the ground. A century ago, this was incredibly rare. The records provide the context for the finds and allow scholars to study the material in a way they could not otherwise. With jewelry, such as necklaces and bracelets, this can be particularly important because the original strings do not survive, but the position in which beads were discovered allows them to be reconstructed accurately. This would be impossible without the photos.

JW: Lying at the conduit of trade between East Africa, Arabia, India, and the Mediterranean Sea, Nubia was celebrated in antiquity for its exotic luxury goods cast in silver, bronze, and especially, gold.

When viewing ancient Nubian jewelry, which singular attributes or characteristics stand out in your opinion? What distinguishes Nubian jewelry from those of neighboring civilizations?

DD: One thing that stands out is how cosmopolitan a place ancient Nubia was. It was in no way a backwater. At various points in time, influences from central Africa were mixing with those from Egypt, Greece, Rome, the Near East, and the Red Sea. Influences were always moving back and forth. During certain periods, such as the eighth century BCE when Nubian kings ruled Egypt, Egyptian motifs are very prominent. At other times, they are much less visible.

In terms of technique, Nubian jewelers were incredibly innovative, often much more so than the Egyptians. Particularly during the Meroitic Period — roughly the third century BCE through the fourth century CE — they were very much ahead of their time, investigating new glassmaking technology and experimenting with a whole range of enamel techniques.

Bracelet with image of Hathor 100 B.C. Gold, enamel. Harvard University—Boston Museum of Fine Arts Expedition. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Another characteristic of Nubian jewelers throughout their history is an interest in unusual and exotic materials. Some types of stones were inherently rare, others had to be imported from as far away as what is now Turkey and Afghanistan, and others were not typically used for jewelry. Color seems to have had special significance; one eighth century BCE queen, Khensa, was buried with a fascinating collection of unusual stones and fossils, some in their original state and some worked into jewelry.

Nubians, at least from the first millennium BCE onwards, have an aesthetic of female beauty that differs strikingly from that of the Egyptians. It is well expressed in a series of large, faience amulets found among the burial goods of early Napatan queens (c. eighth century BCE). One example features a nude, winged goddess crowned with a sun disc, a pair of horns, and double plume. The goddess is notably full figured, with the sensual curves of the breasts, abdomen, and thighs suggesting fertility. Powerful women with similar proportions are seen elsewhere in Nubian art as well.

JW: Nubian artisans employed techniques that would not be reinvented in Europe for another thousand years. What were these techniques, and how did Nubian artisans attain such a high degree of sophistication? Additionally, aside from precious metals, what other materials did Nubian artisans routinely utilize?

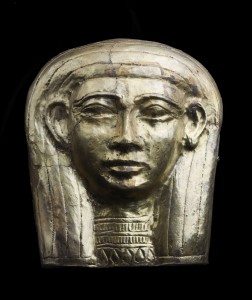

Mask of Queen Malakaye 664–653 B.C. Gilt silver. Harvard University—Boston Museum of Fine Arts Expedition. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

DD: Different techniques were used in different periods. Some of them were never replicated until modern scientists and conservators could analyze their chemical composition in recent years. Others, like certain types of enamels, were independently discovered centuries later, as you point out.

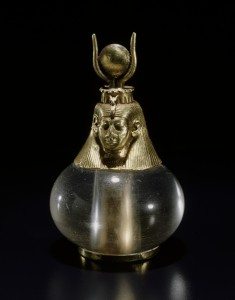

During the period we know as Classic Kerma — about 1700-1550 BCE — jewelers produced blue-glazed quartz beads, made from clear quartz crystals (rock crystal). They were shaped into spheres, pierced, coated with a vitreous glaze, and then heated. The resulting beads are brilliantly translucent. However, these beads were not easy to produce. Reisner uncovered a workshop with large numbers of beads that had cracked and broken during the firing process. Without a doubt, the people of Kerma clearly thought it was worth the trouble. Kerma artisans used a similar technique to glaze sculpture and also natural crystals that were fashioned into pendants worn around the neck or waist. Quartz must have held a special religious significance, possibly as a result of its association with the mining of gold, which was itself believed to be imbued with magical properties.

Much later, during the Meroitic Period, Nubian craftsmen experimented with several types of enamels, as I mentioned earlier. Among the most difficult and unusual are the backless “stained glass window” technique (plique à jour) the earliest known example of which comes from Nubia and dates to the first century BCE. Another technique in which Meroitic jewelers were ahead of their time is champlevé enameling, in which areas carved out of the metal backing were filled with powdered glass that fused upon heating.

Amulet of Maat 743–712 B.C. Gilded silver and malachite. Harvard University—Boston Museum of Fine Arts Expedition. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Glassmaking — at the time a new technology — was very sophisticated in Meroitic Nubia. Particularly complex and impressive are what we call “stratified eye beads,” which are multi-colored beads with spots or circular rings representing eyes. As Yvonne explains them, they were formed by applying drops of molten glass onto the body of a heat-softened glass bead and then pressing the drop into the matrix. Certain of these beads also feature criss-crossing gold bands created by carving into the blue glass matrix, then setting thin strips of gold sheet into the channels, and covering the gold with a thin, protective coat of clear glass (en résille sur verre enamel). Each bead would have taken hours to produce.

JW: Symbolism certainly played a guiding role in iconography and ritual use. As I understand it, ancient Nubians valued possessions, like jewelry, not only for their inherent beauty, but also because they were imbued with magical meanings. Could you perhaps share more information about how ancient Nubians perceived jewels and jewelry?

DD: In ancient Nubia, a principle role of jewelry was amuletic, meaning that the raw materials or the form of an ornament were believed to protect the wearer from malevolent forces. Unfortunately, because many Nubian cultures did not have a written language until relatively late in their history and because scholars are still unable to translate the Meroitic language, we can only guess at other meanings based on representations of jewelry in art or from the archaeological context.

Double Hathor head earring 90 B.C.–50 A.D. Gold, enamel. Harvard University—Boston Museum of Fine Arts Expedition. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Gold clearly seems to have been sacred as well as intrinsically valuable, probably because of its imperishability. As I mentioned, quartz was regarded as having divine properties probably because it was found alongside gold. An intriguing adornment, the alluvial (placer) nugget jewel, is evidence of the importance of gold in Nubia. One example, the largest so far recovered from ancient Nubia, was found near the neck of a deceased male. The 50 gram specimen of solid gold has not been worked other than with the addition of a hand-fabricated gold bail to allow for stringing. So clearly the gold itself, rather than the form it took, was important.

Other stones were selected for unusual colors or shapes. A good example is an eighth century BCE amulet of Thoth, the god of moon, as well as writing and knowledge. It is made of blue chalcedony, a rare form of quartz mined in what is present-day Turkey and used in the manufacture of Babylonian seals and small, precious sculptures. It’s possible the Nubian associated its unusual silvery blue color with a lunar deity.

Pendant with ram-headed sphinx 743–712 B.C. Gilded silver, lapis lazuli, and glass. Harvard University—Boston Museum of Fine Arts Expedition. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Certain animals were associated with royal power, in particular lions and rams. Both are recurrent motifs in Nubian jewelry. The ram, representing the supreme deity Amen (Egyptian: Amun), was featured on necklaces and earrings worn by Nubian rulers and was eventually adopted by a larger segment of the population. Ram-headed sphinxes combine the forces of both animals.

JW: Which items do you believe will surprise visitors to this exhibition, and why? Furthermore, what do you hope museum-visitors walk away with after having seen these exquisite creations?

DD: The Nubian cultures remain surprisingly unfamiliar to most people, especially when compared to their much more famous Egyptian neighbors. I think visitors will be impressed by their sophistication and inventiveness as well as the beauty of their creations. I think many people will also be struck by how contemporary some of the pieces look. I can easily envision people wearing them today.

Signet ring 200–320 A.D. Gold. Harvard University—Boston Museum of Fine Arts Expedition. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

I hope that visitors will leave with a better understanding and appreciation of the Nubians and that the exhibition will whet their appetites to learn more about ancient Nubia. The study of Nubia has expanded exponentially in the past few decades and our knowledge about the Nubians is so much greater than it was at the time of Reisner’s excavations. His careful records remain crucially important to scholarship but can now be evaluated in the light of a century of research that has taken place since. Nubia really deserves to be much better known.

JW: Curator Denise Doxey, I thank you so much for speaking to us about a most intriguing exhibition! We look forward to covering the Museum of Fine Art, Boston’s next show on ancient art in the near future.

DD: Thank you! And you won’t have to wait long to hear about our latest installation. The MFA just opened three beautiful galleries of ancient Greek art, focusing on Homer, the worship of Dionysos, and the theater. I strongly encourage you to check them out.

Hathor headed crystal pendant 743–712 B.C. Gold, rock crystal. Harvard University—Boston Museum of Fine Arts Expedition. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Be sure to check out Ancient History Encyclopedia’s review of the Gold and the Gods: Jewels of Ancient Nubia exhibition catalogue. Gold and the Gods: Jewels of Ancient Nubia will be on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston until May 14, 2017.

Image credits and captions: Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Denise M. Doxey is Curator, Ancient Egyptian, Nubian and Near Eastern art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Before joining the staff of the MFA in 1999, she was Keeper of the Egyptian Section at the University of Pennsylvania Museum. She has excavated in Greece and Egypt, and has taught Egyptology courses at the University of Pennsylvania and Harvard University. She has published numerous books and articles about ancient Egyptian and Nubian art, religion, and history. Her most recent books are The Jewels of Ancient Nubia (with Yvonne J. Markowitz) and The Secrets of Tomb 10A: Egypt 2000 BC (with Rita E. Freed, Lawrence M. Berman and Nicholas S. Picardo).

All images featured in this interview have been cited and images from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston have been provided to Ancient History Encyclopedia solely for the purposes of this interview. Unauthorized reproduction of text and images is strictly prohibited. Special thanks is extended to Ms. Amelia Kantrovitz, Media Relations Manager at Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, for facilitating this interview. Mr. James Blake Wiener was responsible for the editorial and publication process. The views presented here are not necessarily those of the Ancient History Encyclopedia (AHE). All rights reserved. © AHE 2014. Please contact us for rights to republication.