I was attending an international neurology conference in Istanbul, Turkey. I had two days left, and I thought to myself: “How about shooting some artifacts in the Istanbul Archaeological Museums?” I visit Istanbul every now and then and this museums’ neighborhood is one of my favorite spots. It’s on a hill in the same complex as the famous Topkapi Palace.

It is a group of three museums (Archaeological Museum, Ancient Orient Museum, and Tiled Kiosk Museum). The group lies on the European side of Istanbul at Sultanahmet/Fatih district. You should not miss the nearby Gulhane Park, Topkapi Palace, and Hagia Sofia; all are within the same area!

There is a single entrance for all of the museums. The opening hours are from 9 AM to 5 PM. Monday is the Museum’s holiday. The price of the ticket is 15 Turkish Lira (circa 6.50 USD; 5.50 EUR). You can visit the three museums with this ticket. Excellent deal!

My first station was the Ancient Orient Museum. The Museum’s logo says that it is founded in 1917 CE. It is a 1-floor building and the artifacts are categorized according to their origin/civilization.

Once you pass through the information desk, you will find some artifacts from the pre-Islamic Arabian Peninsula. Next, comes the ancient Egyptian section. And, then turn right; a small stela of Nabonidus, the last king of Babylon is erected and lions from the Processional Street of Babylon flank the way. Step by step, you will encounter artifacts from Anatolia, Urartu, and Mesopotamia.

Granite stela of Nabonidus, king of Babylon, 555-539 BCE. From Babylon, Mesopotamia. It narrates the religious activities of the king and the harassment of enemies to city of Babylon and other cities. In the background, the standing/striding lions of the Processional Street of Babylon appear. Glazed bricks from Babylon (modern-day Babel Governorate, Iraq). Reign of king Nebuchadnezzar II, 602-562 BCE. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Marvelous large basalt wall reliefs and stelae which date back to the Hittite Empire period from Urartu can be seen. Some masterpieces drew my attention:

- A Code of Hamurabi tablet,

- a statue of Shalmaneser III,

- the oldest love poem tablet,

- wall reliefs from the north-west palace at Nimrud,

- Babylonian Processional Street wall reliefs (lion, sirrush, and auroch reliefs),

- a stela of Nabonidus,

- a stela of Sennacherib,

- the Kadesh treaty tablet,

- and a complete ancient Egyptian grave’s content.

Many tablets from several periods within Mesopotamia were displayed in large single case. A multitude of Neo-Assyrian artifacts (necklaces, amulets, bracelets, and fibulae) I found, too.

It is not that large of a museum, but the museum’s content is very impressive! I always enjoy visiting it! I shot many, many, and many pics. I was exhausted; 2 more museums to visit. There is small cafeteria within the courtyard of the museums; I sat there, and ordered some food and drink!

Arabian Votive Statues

Votive statues from the Arabic Peninsula. Pre-Islamic, 4th to 1st centuries BCE. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Ptah-Seker Statues

These are wooden statues of Ptah-Seker. Ptah was the protector god of artisans while Osiris was the god of the underworld. Seker (bird) was the god of the cemetery. When a person dies, a piece from his body is taken, embalmed and placed in a box, and then sealed with a wax. Thereafter, a Seker bird is put on the top. Ancient Egyptians believed that the deceased person becomes immortal by doing these steps. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Egyptian Grave

Grave finds from ancient Egypt. In this grave, we can see coffins, mummies, canopic jars, head part of a wooden coffin, baskets for beads, wooden chest for ushabties, and beadwork covers. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Statue of Lugal-Dalu

Statue of Lugal-dalu. The cnueform inscriptions on the right shoulder of this man say that this man is Lugal-dalu and is the king of Adab, and that the statue was devoted to Esar, the great god of that city. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Hittite Banquet

This basalt stela depicts a banquet scene. It is inscribed with hieroglyphic inscriptions. From Maras (modern-day Kahramanmaraş, southern Turkey). Late Hittite period, 9th century BCE. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Hittite Double Sphinx

A double sphinx statue. This was found at the entrance to the palace number 3 at Sam’al. In the background, a basalt wall relief of 4 musicians appear. On the left, a basalt statue of a lion can been seen partially. All are from Sam’al (modern-day Zincirli Hoyuk, southern Turkey). Late Hittite period, 8th century BCE. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Hittite Reliefs

Basalt wall reliefs from the western side of the citadel gate at Sam’al (modern-day Zincirli Höyük, southern Turkey). Late Hittite period, 9th century BCE. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Stela of Shamash-Res-Usur

Limestone stela of Shamash-res-usur (governor of Mari and Suhi). He is praying in front of the gods. From the palace museum at Babylon, modern day Babel Governorate, Iraq. 8th century BCE. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Stela of Sennacherib

This is the upper part of the limestone stela of Sennacherib, king of Assyria. The king is praying in front god symbols. From Kuyunjik (modern-day Ninawa Governorate, Iraq). 705-681 BCE. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

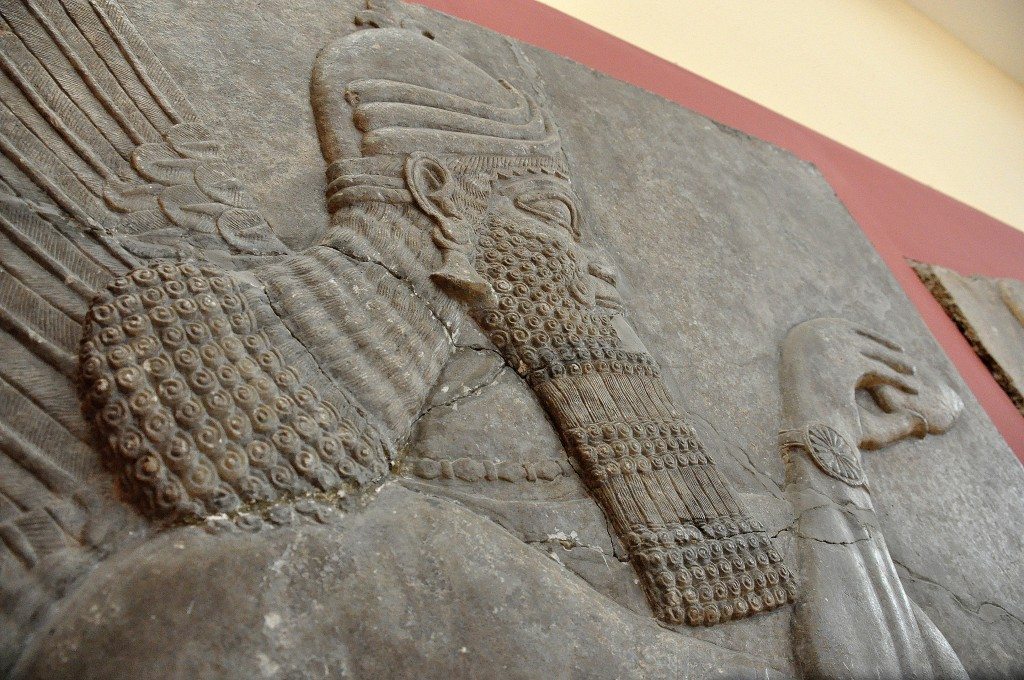

Winged Apkallu

Alabaster bas-relief of a human-headed and winged Apkallu (sage). From the north-west palace of king Ashurnasirpal II at Nimrud (ancient Kalhu; Biblical Calah), northern Mesopotamia, Iraq. 883-859 BCE. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Shalmaneser III

Basalt statue of Shalmaneser III, king of Assyria from 858-824 BCE. The cuneiform inscriptions on the statue narrate a brief account of the king’s genealogical titles and characteristics. The inscriptions also say that the king’s military campaigns against the lands of Urartu, Syria, Namri, Que, and Tabal have come to an end. From Assur (modern-day Qala’at Sharqat, Iraq). In the background (and to the left of the statue) , reliefs of a sirrush and an auroch from the processional street of Babylon appear. At the left edge of the image, a head of a lamassu can be seen. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Stela of Naram-Sin

Part of the diorite stela of Naram-Sin, king of Akkad. 2254-2218 BCE. From Pir Huseyin (Diyarbakir), southern Turkey. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.