Roman mosaics decorated luxurious domestic and public buildings across the empire. Intricate patterns and figural compositions were created by setting tesserae — small pieces of stone or glass — into floors and walls. Scenes from mythology, daily life, nature, and spectacles in the arena enlivened interior spaces and reflected the cultural ambitions of wealthy patrons. Introduced by itinerant craftsmen, mosaic techniques and designs spread widely throughout Rome’s provinces, leading to the establishment of local workshops and a variety of regional styles.

Drawn primarily from the Getty Museum’s collection, Roman Mosaics across the Empire at the Getty Villa in Los Angeles, California, presents the artistry of mosaics as well as the contexts of their discovery across Rome’s ever growing empire — from its center in Italy to provinces in North Africa, southern France, and ancient Syria. In this exclusive interview, James Blake Wiener of Ancient History Encyclopedia speaks to Dr. Alexis Belis, assistant curator in the Department of Antiquities at the J. Paul Getty Museum, about the various kinds of mosaics found within the former Roman Empire.

Floor Panel, A.D. 4th century. Roman mosaic, Stone tesserae. H: 129.5 to 174 × W: 148 to 87.6 × D: 9.5 cm (51 to 68 1/2 × 58 1/4 to 34 1/2 × 3 3/4 in.). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Villa Collection, Malibu, California. Image courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum.

JW: Why do mosaics so captivate and enthrall us, Dr. Alexis Belis? Additionally, why did the Getty Villa decide to undertake an exhibition devoted to Roman mosaics?

AB: Above all, mosaics are visually impressive in their size and appearance. They offer a vivid picture of ancient Roman life, revealing how Romans lived in surroundings filled with art and imagery. Their subjects — frequently dramatic narrative scenes that range from mythological and literary subjects to images of athletic contests and daily life — provide insight into Roman cultural values and artistic preferences. Since many are preserved in their original architectural contexts, usually decorating floors, mosaics also give us an idea of how the Romans experienced interior spaces.

The Getty Villa decided to organize an exhibition not just on Roman mosaics, but specifically on the Getty’s collection of Roman mosaics. Most have been in storage for decades, and some have never been displayed at all. The collection is significant because many of the mosaics were excavated during the early twentieth century and have known findspots. We also had the opportunity to present new research on the mosaics in an online publication — Roman Mosaics in the J. Paul Getty Museum.

Lion Attacking an Onager. Roman mosaic, from Hadrumetum (present-day Sousse, Tunisia), A.D. 150-200. Stone and glass. 38 ¾ x 63 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Villa Collection, Malibu, California. Image courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum.

JW: Mosaics made their initial appearance during the Hellenistic Period thanks to the Greeks, but it was under the Romans that they became omnipresent across the Mediterranean world and beyond.

In what ways did the Romans differ from their Greek predecessors in their creation and appreciation of mosaics as an art form?

AB: While the Greeks refined the art of figural mosaics using pebbles embedded in mortar, the Romans took the art of mosaics to a completely new level, using tesserae of brightly colored stone and glass to create intricate patterns and figural scenes.

Mosaics are closely aligned with Roman culture, and the use of mosaic floors in this technique followed the spread of Roman power throughout the empire. We find a combination of Italian styles and local traditions in mosaic designs in many of the provinces, especially in what is present-day France and North Africa.

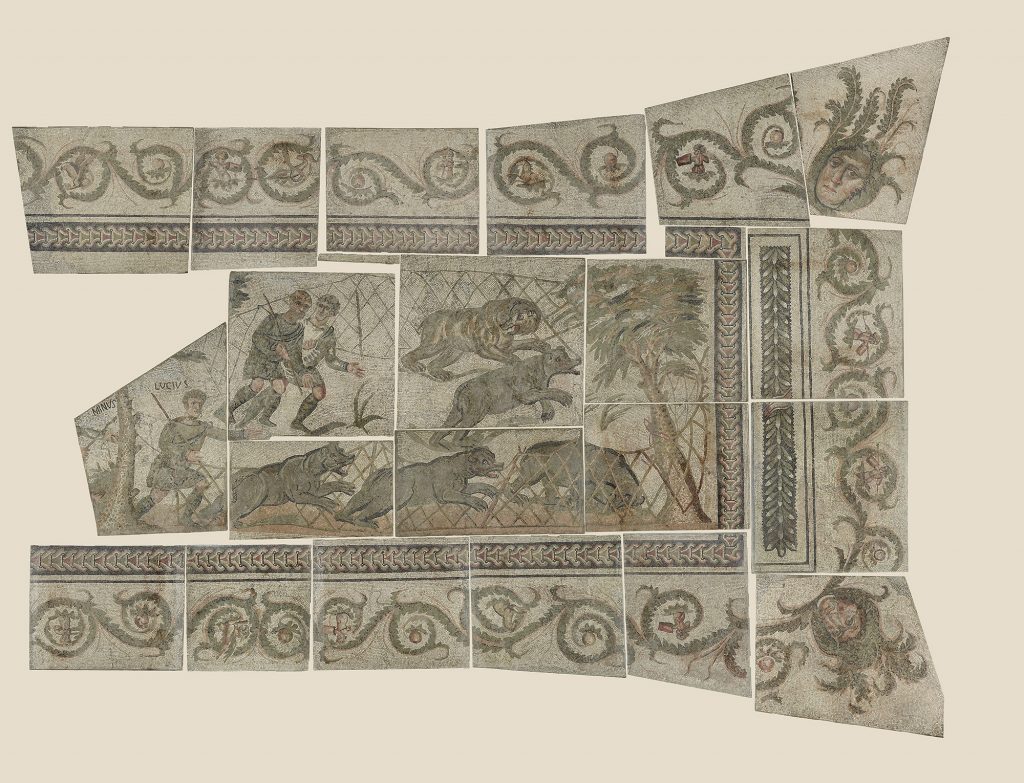

Bear Hunt. Roman mosaic, from Baiae. Italy, A.D. 300-400. Stone. 260 ¼ x 342 1/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Villa Collection, Malibu, California. Image courtesy of the The J. Paul Getty Museum.

JW: In your own words, what else do mosaics tell us about ancient Rome and daily life across the empire? Mosaics were certainly a means through which wealthy Roman delineated their wealth and cultural pursuits, but what else did they convey and what secrets do they conceal?

AB: Mosaics tell us a great deal about ancient architecture. Because of their durability and the fact that they were built into the foundations of buildings, mosaics are among the best-preserved forms of Roman art. The locations and architectural settings of many mosaics have been recorded, and their placement sometimes relates to the function of the spaces they decorated.

For example, the Getty’s mosaic from Antioch, once decorated the entryway of a small public bath building. Other mosaic floors of the building depict busts of Soteria and Apolausis, the Greek personifications of Salvation and Enjoyment, respectively. Such themes would have been appropriate for spaces where Romans gathered for social interactions, entertainment, and to experience the revitalizing waters of the baths.

Some mosaics encourage the viewer to experience a space or room from different perspectives. A mosaic in the exhibition from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art has a central narrative scene bordered on all four sides by a hunting frieze. As the viewer follows the hunters and animals they walk around the mosaic and look at the images from different angles.

Combat between Dares and Entellus. Gallo-Roman mosaic, from Villelaure, France, A.D. 175-200. Stone and glass. 81 7/8 x 81 7/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Villa Collection, Malibu, California. Image courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum.

JW: Which scenes or subject matter did the Romans favor most when creating mosaics, Dr. Belis?

AB: Scenes from Greek and Roman mythology as well as literature were especially prevalent. Two mosaics from the same villa in Gaul, found near the modern town of Villelaure, France, depict highly original scenes from Roman literature: a scene of Diana and Callisto from Ovid’s Metamorphoses (on loan from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art), and a boxing match between Dares and Entellus from Virgil’s Aeneid. At the same time, a mosaic in the Getty’s collection found at Saint-Romain-en-Gal, also in France, represents the popular Greek myth of Orpheus charming the animals.

Scenes of hunting and capturing animals for the arena were also widespread, as shown in an enormous mosaic of a bear hunt from Baiae on the Bay of Naples. Wealthy Romans often financed the capture of wild animals for spectacles in the arena, which were therefore fitting subjects for mosaic floors in luxurious private villas.

Mosaics with these themes frequently decorated dining rooms and reception areas — spaces in which the owner could entertain and impress guests with his wealth, prestige, and social status.

Peacock Facing Left. Roman mosaic, from Syria, possibly Emesa (present- day Homs), A.D. 400 – 600. Stone 77 ½ x 45 ½ in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Villa Collection, Malibu, California, Gift of William Wahler. Image courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum.

JW: You mentioned that Roman Mosaics across the Empire consists of mosaics drawn largely from the Getty Museum’s own collection. Among these, which do you find remarkable and worthy of further discussion in particular? Is there a pièce de résistance?

AB: Since most of the objects in the exhibition are from the Getty Museum’s own collection, they also give us a sense of J. Paul Getty’s own interest in mosaics. Getty acquired his first Roman mosaic (the one depicting a bust of Orpheus surrounded by animals) in 1949, and had it installed over the floor of one of the rooms in his new museum — a Spanish Colonial style ranch house where his collection was displayed until the Getty Villa opened in 1974.

The two mosaics from Villelaure, France, which are on view together for the first time in over a century, are especially interesting. They are remarkable in part because they decorated adjacent rooms of the same villa, revealing the diversity of the owner’s preferences. However, the Getty’s mosaic of Dares and Entellus also suggests a regional connection, as this uncommon scene occurs in at least four other mosaics in southern France.

Another significant mosaic is the one from the small bath complex at Antioch, which depicts a hare eating grapes and small birds surrounded by elaborate geometric designs. Since it was discovered during a series of campaigns in the 1930s, we have excavation photos that document the appearance of the mosaic in situ before it was removed from the building.

JW: Dr. Belis, I thank you so much for speaking with me about this lovely exhibition. I wish you many happy adventures in research!

AB: Thank you, James — I have really enjoyed talking with you about the exhibition!

Roman Mosaics across the Empire is on show at the Getty Villa in Los Angeles, California until September 12, 2016. Click here to read and download the gallery text that accompanies the exhibition in PDF.

Dr. Alexis Belis is currently assistant curator in the Department of Antiquities at the J. Paul Getty Museum. She received her BA in art history and music from the University of Notre Dame in 2000, and her PhD in classical archaeology from Princeton in 2015. She has been an intern at the Princeton University Art Museum and at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology, and served as a research assistant at the Harvard Art Museums, working on their collection of ancient bronzes. She has contributed to several museum handbooks, including a publication of the Classical collection of the Snite Museum of Art at the University of Notre Dame.

Dr. Alexis Belis is currently assistant curator in the Department of Antiquities at the J. Paul Getty Museum. She received her BA in art history and music from the University of Notre Dame in 2000, and her PhD in classical archaeology from Princeton in 2015. She has been an intern at the Princeton University Art Museum and at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology, and served as a research assistant at the Harvard Art Museums, working on their collection of ancient bronzes. She has contributed to several museum handbooks, including a publication of the Classical collection of the Snite Museum of Art at the University of Notre Dame.

All images featured in this interview have been attributed to their respective owners. Images lent to AHE by the J. Paul Getty Museum have been done so as a courtesy. Interview edited by James Blake Wiener for AHE. Special thanks is extended to Ms. Desiree Zenowich, Senior Communications Specialist at J. Paul Getty Museum, for facilitating this interview. Unauthorized reproduction is strictly prohibited. All rights reserved. © AHE 2016. Please contact us for rights to republication.