The assassination of Gaius Julius Caesar on March 15, 44 BCE is one of the most dramatic and notorious events in Roman history. Many of us living in Anglophone nations are familiar with the events of Caesar’s demise thanks in large part to William Shakespeare’s play, Julius Caesar. However, Shakespeare dramatized only a few vignettes of a story written in cold blood. In The Death of Caesar: The Story of History’s Most Famous Assassination, by acclaimed military historian Barry Strauss, the reader learns how disaffected politicians and officers carefully planned and hatched Caesar’s assassination weeks in advance, rallying support from the common people of Rome. One is also introduced to fascinating character of the man who truly betrayed Caesar — the wealthy and intelligent Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus. In this exclusive interview to commemorate the Ides of March, James Blake Wiener, Communications Director at Ancient History Encyclopedia (AHE), speaks with Dr. Barry Strauss about his new title and why he chose to revisit the world of late Republican Rome.

JW: Dr. Barry Strauss, welcome to Ancient History Encyclopedia and thank you for speaking to me about The Death of Caesar: The Story of History’s Most Famous Assassination as we approach the Ides of March. Congratulations on the publication of your new title!

I am curious to know what compelled you to investigate the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 BCE? Why reexamine this very bloody episode in Roman history?

BS: Thanks, first of all, for your generous words and for this opportunity to chat, James.

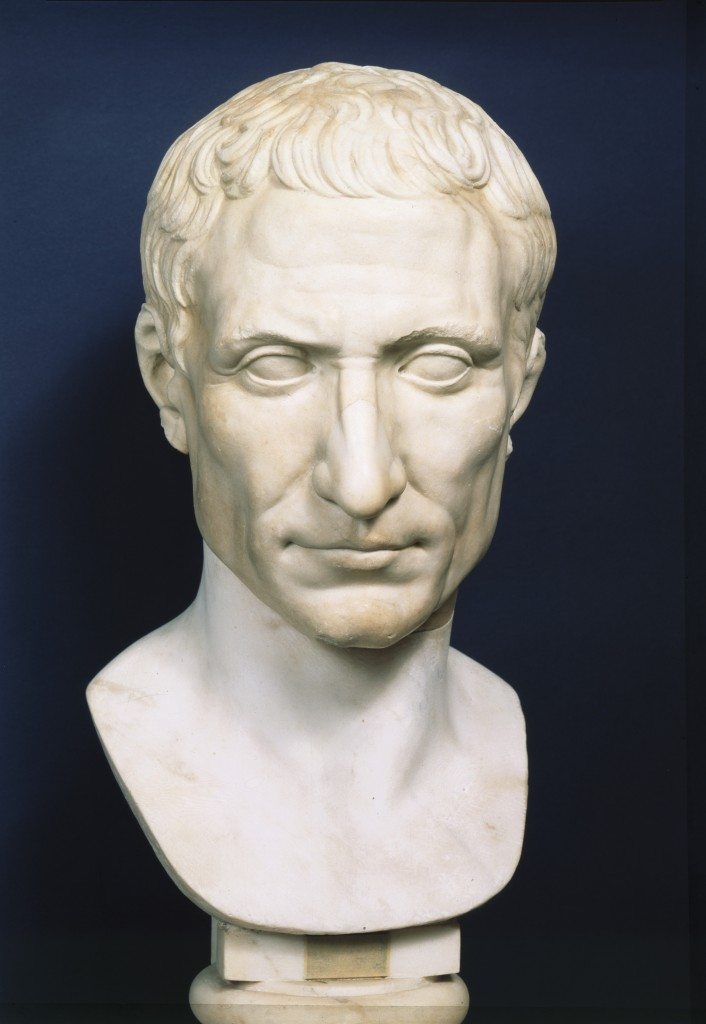

This is a great time to be working on Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE). For a long time, Caesar was unfashionable; after the Second World War, dictators did not bear thinking about, understandably. Now there has been a veritable renaissance of Caesar studies. Scholars have also been rethinking Roman politics, with the result of putting the people back into the equation. It’s also a great era for ancient military history. So, all in all, I’ve been fortunate enough to have the research of many superb scholars to work with.

I came to the question of Caesar’s assassination as a military historian. It seemed to me that the military aspect of the assassination was understudied. I began with the role of the gladiators on the Ides of March, when they seemed to play a paramilitary function, but precisely how was unclear. The gladiators in turn led to many other questions, some going back to the Gallic War (58-50 CE) and others looking ahead to the civil war that followed Caesar’s death. And they also led me to ask new questions about the killing itself and how it unfolded.

JW: Tell us about the research process you undertook in order to write The Death of Caesar — which ancient texts did you consult to determine the most accurate sequence of the events surrounding the assassination of Caesar? Were there any sources that you enjoyed working with in particular? If so, which ones and why?

BS: I consulted all the ancient accounts of the assassination, especially the five most detailed ones: Plutarch (c. 46-c. 120 CE), Suetonius (c. 66-c. 122 CE), Appian (c. 95-c. 165 CE), Cassius Dio (c. 155-235 CE) and, last but not least, Nicolaus of Damascus (c. 64 BCE-14 CE). In fact, Nicolaus’s Life of Augustus proved to be the most important of these sources for me. Although we have only an ancient abridgment of part of this work, it focuses on Caesar’s assassination. Nicolaus had his biases; he worked for Augustus, among other things. But important recent research shows that Nicolaus was learned, incisive, and a serious thinker. In addition, he was actually alive at the time of the Ides of March: His is the earliest detailed account to survive, and he had the chance to speak to some of those who were there that day. In the tradition of Aristotle and Thucydides, whom Nicolaus studied, he offers a more realistic version of the assassins than the rather idealistic picture in, say, Plutarch, the source who most influenced William Shakespeare (1564-1616 CE).

I also visited all the relevant archaeological sites in Rome and some important battle sites of Caesar’s career. Additionally, I had the chance to examine some of the key artifacts in museums, including the famous “Ides of March” coin.

JW: Assassination colors the long course of Roman history, Dr. Strauss. What distinguishes the assassination of Caesar from those of other political assassinations in the late Republican era; namely, the assassinations of Tiberius Gracchus (c. 169/164-133 BCE) and Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus or “Pompey” (106-48 BCE)?

BS: Pompey was assassinated on a foreign shore at the order of a foreign ruler.

Like Caesar, Tiberius Gracchus was murdered by a group of prominent senators in Rome. They acted openly, however, while Caesar’s assassins engaged in a secret plot. Gracchus was murdered in a riot at an electoral assembly; Caesar was killed in the Senate. Dozens if not hundreds of Gracchus’s supporters were killed with him while Caesar alone was targeted. The military dimension also makes a difference: Caesar was killed in the interval between a civil war and a foreign war, and his generals were among the leading assassins. Finally, Gracchus was killed by his enemies, while many of Caesar’s assassins were his disillusioned friends.

Morte di Giulio Cesare (“Death of Julius Caesar”) by Vincenzo Camuccini, 1798 CE. (Courtesy of Simon & Schuster.)

JW: Dr. Strauss, I was wondering if you might tell us a bit more about the background and character of Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus (85/81-43 BCE). While reading The Death of Caesar it becomes clear that it was Decimus, not Brutus, who truly betrayed Caesar, and that Decimus was the lynchpin in the plot to assassinate Caesar. Aside from his involvement in Caesar’s death, he’s certainly a most intriguing character.

BS: Like Caesar or his distant cousin Brutus (85-42 BCE), Decimus came from an old and noble Roman family. Unlike Brutus, Decimus built his career as Caesar’s man. He was Caesar’s most successful admiral both in the Gallic War and in the Civil War (49-45 BCE), and Caesar chose Decimus to govern Gaul as his deputy while Caesar fought in the east and in North Africa. We get a sense of Decimus from his letters to Cicero: he was educated, military, terse, tough, focused on his reputation and honor, stung by those who (in his opinion) insulted him. He married an ambitious woman who came from a family that had supported Caesar’s rival, Pompey, during the Civil War. Why did Decimus turn on Caesar? I suspect it was because Caesar overlooked him in favor of Octavian, a much younger and less experienced man. Caesar chose Octavian as his second-in-command in the new war against Parthia. I also suspect that Decimus resented Caesar’s unwillingness to let him celebrate a triumph for his victory over the tribe of the Bellovaci in Gaul.

As you say, Decimus was the closest to Caesar of all the assassins and his betrayal was the most egregious. That is little known, as is Decimus’s remarkable career after the assassination. He allied with Octavian and stoutly withstood Mark Antony’s attack during the siege of Mutina (present-day Modena) in northern Italy in winter 44-43 BCE. When Mark Antony (83-30 BCE) was forced to flee and regroup, Decimus boldly followed him over the Alps into Gaul. But the political winds shifted and Octavian dropped Decimus for Antony. Eventually Decimus’s soldiers abandoned him and Decimus was forced to try to escape disguised as a Gaul. (Decimus actually spoke Gaulish.) He was caught and executed in September 43 BCE, ending a wild ride of a career.

The most enjoyable aspect of writing this book, besides living in Rome, was wrestling with the character of Julius Caesar. What a challenge it is to understand the character of one of the most brilliant but violent of men in history!

JW: You contend that there were a series of seminal moments in which public and senatorial perception of Caesar soured, thus leading the way to Caesar’s own assassination. When did these moments occur, and why do you feel they are important in our understanding of Caesar’s subsequent and violent downfall?

BS: There were a series of seminal moments in the months from October 45 BCE to March 44 BCE in actuality. The Roman public was able to see for itself just how king-like Caesar had become. The historian Livy highlighted three things in winter 44 BCE that soured the public and the senate: Caesar’s refusal to stand to greet a delegation of senators who came to grant him new honors, Caesar’s attack on the two tribunes who punished a man for calling Caesar “king” on January 26, 44 BCE, and Caesar’s ostentatious refusal of the kingship when it was offered to him by Antony (83-30 BCE) at the Lupercalia Festival on February 15, 44 BCE — which many saw as a trial balloon floated by Caesar itself. In addition to Livy’s three moments, I would also add Caesar’s acceptance of the unprecedented title of “Dictator in Perpetuity” and the presence in Caesar’s villa just outside Rome of his mistress, the queen of Egypt — Cleopatra VII (r. 51-30 BCE). All of these persuaded many that Caesar planned to replace the Roman republic with a monarchy in all-but-name.

JW: Would you say the assassination of Caesar is a decisive event in European or even world history, Dr. Strauss? Is it fair to say that Caesar’s political downfall and death led to the rise of imperial Rome and the eventual triumph of Octavian, later Augustus Caesar (r. 27 BCE-14 CE)?

La Mort de César (“The Death of Caesar”) by Jean-Léon Gérôme, c. 1859–1867. This painting depicts the aftermath of the attack with Caesar’s body abandoned in the foreground as the senators celebrate the success of their murder in the background. (Courtesy of Simon & Schuster.)

BS: The assassination certainly was a historical watershed. It meant that, at a minimum, those who wanted to save the Republic would have to make a number of compromises to win over the soldiers. But they failed on the battlefield and in the diplomacy that preceded battle, with the result that Octavian eventually triumphed and became Augustus Caesar. That triumph wasn’t inevitable, and fortune had something to do with it, but Octavian was a ruthless genius with the talent of the Julian family. His opponents were good but not as good.

JW: Before concluding our interview, what do hope readers come away with after reading The Death of Caesar? Additionally, what was the most enjoyable aspect of writing this book?

BS: Through Shakespeare we think of the assassination of Julius Caesar as a political event. I hope that my readers see it as a soldier’s story. Rome was a militarized city in March 44 BCE, full of Caesar’s veterans and new soldiers ready to march off to war again. Caesar’s own generals organized the plot and carried out the murder. Ironically, they weren’t shrewd enough to give their men — Caesar’s veterans — a raise afterwards, and that, as much as anything else, was the assassins’ undoing.

The most enjoyable aspect of writing this book, besides living in Rome, was wrestling with the character of Julius Caesar. What a challenge it is to understand the character of one of the most brilliant but violent of men in history!

JW: Dr. Strauss, I thank you for your time and I wish you many happy adventures in research. I hope that we can speak again when your next publication is released.

BS: Thank you. You asked great questions and I appreciate the challenge. I’d love to have the chance to speak again for my next book.

JW: Thank you so much, Dr. Strauss! I will be sure to invite you back.

[embedyt]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6YIRQ6b52rs[/embedyt]

Dr. Barry Strauss is a leading expert on ancient military history. He has written and edited several books, including Masters of Command, The Battle of Salamis, The Trojan War, and The Spartacus War. His latest publication is The Death of Caesar: The Story of History’s Most Famous Assassination, which explores the milieu of late Republican Rome and the assassination of Julius Caesar. His books have been translated into nine languages. Strauss holds fellowships from the American Academy at Rome, the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, the American Enterprise Institute, the German Academic Exchange Program, the Korea Foundation, the MacDowell Colony, and the National Endowment for the Humanities. He is the recipient of Cornell’s Clark Award for Excellence in Teaching. Currently, he teaches courses on the history of ancient Greece, war and peace in the ancient world, history of battle, introduction to military history, and specialized topics in ancient history at Cornell University.

Dr. Barry Strauss is a leading expert on ancient military history. He has written and edited several books, including Masters of Command, The Battle of Salamis, The Trojan War, and The Spartacus War. His latest publication is The Death of Caesar: The Story of History’s Most Famous Assassination, which explores the milieu of late Republican Rome and the assassination of Julius Caesar. His books have been translated into nine languages. Strauss holds fellowships from the American Academy at Rome, the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, the American Enterprise Institute, the German Academic Exchange Program, the Korea Foundation, the MacDowell Colony, and the National Endowment for the Humanities. He is the recipient of Cornell’s Clark Award for Excellence in Teaching. Currently, he teaches courses on the history of ancient Greece, war and peace in the ancient world, history of battle, introduction to military history, and specialized topics in ancient history at Cornell University.

All images featured in this interview have been attributed to their respective owners. Images lent to Ancient History Encyclopedia by Simon & Schuster and Dr. Barry Strauss have been done so as a courtesy for the purposes of this interview. Unauthorized reproduction prohibited. A heartfelt thank you is extended to Mr. Stephen Bedford at Simon & Schuster for helping arrange this interview. The views presented here are not necessarily those of the Ancient History Encyclopedia. All rights reserved. © AHE 2015. Please contact us for rights to republication.